Today we travel to a future where all animal testing is banned. What are the alternatives? What can we do without using animals, and what can’t we do?

Guests:

- Janet D. Stemwedel — professor of philosophy at San Jose State University

- Lawrence Carter Long — communications director at the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund

- Kristie Sullivan — vice president of research policy at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine

- Deepak Kaushal — director of the Southwest National Primate Research Center at Texas Biomedical Research Institute

- Hunter Rogers — researcher at Northwestern University on EVATAR project

Further Reading:

- FDA Animal Testing and Cosmetics

- How did the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act come about?

- Safety Testing History

- Opinion versus evidence for the need to move away from animal testing.

- Ex-Director Zerhouni Surveys Value of NIH Research

- Global trends of animal ethics and scientific research

- The ‘Necessity’ Of Animal Research Does Not Mean It’s Ethical

- Reengineering Translational Science: The Time Is Right

- The ethics of animal research. Talking Point on the use of animals in scientific research

- 1926 The Atlantic: The Ethics of Animal Experimentation

- The Moral Status of Invasive Animal Research

- The ethics and value of responsible animal research

- Science for the People podcast episode: Animal Research Revisited

- Nothing to hide: opening the files on animal research

- Medical progress depends on animal models – doesn’t it?

- Reliability of Protocol Reviews for Animal Research

- Estimates for worldwide laboratory animal use in 2005.

- Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review

- Roadmap to guide progress toward replacing animal use in toxicity testing

- Alternatives to animal testing: A review

- Animal experimentation: A look into ethics, welfare and alternative methods

- What are the Best Animal Models for Testing Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy?

- Long-term neuropathologic changes associated with cerebral palsy in a nonhuman primate model of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Physicians Committee For Responsible Medicine: Animal Testing Alternatives

- Alternatives to Animals Fact Sheet

- EVATAR system

- A microfluidic culture model of the human reproductive tract and 28-day menstrual cycle

- Device Mimicking Female Reproductive Cycle Could Aid Research

- Organ-on-a-chip platforms for drug delivery and cell characterization: A review

- Organ-on-a-chip platforms for studying drug delivery systems

- Recent advances in organ-on-a-chip technologies and future challenges: a review.

- Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation

Actors:

- Maria — Cara Rose de Fabio

- Gaby — Eler de Grey

- Marquis — Rotimi Agbabiaka (check out his new solo show called Manifesto on June 21 at the African American Arts and Culture Complex as part of the National Queer Arts Festival.)

- John — Keith Houston (also check out his karaoke nights in San Francisco)

- Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Special thanks this episode to

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹

Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible… or not so possible future scenario. We always start with a little field trip to the future, to check out what’s going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to experts about how that world we just heard might really go down. Got it? Great!

Before we go to the future, another quick

reminder that if you become a patron between now and June 30th, you get a

surprise in the mail from me! More on that at patreon.com/flashforwardpod. I

won’t talk your ear off about this too much on this episode… so… let’s go to

the future!

This episode we’re starting in the year 2059.

[ding]

Marquis: Okay… I think I have this working

Maria: Yeah it’s working!

[ding]

Gaby: Whoa. You guys look good.

Maria: Pretty cool huh?

Gaby: Do you think John will be able to figure this out?

Maria: It’s not THAT complicated.

Marquis: Is John even going to show up?

Maria: Yeah I texted him earlier.

[ding]

John: Hey guys… whoa. It’s like you’re right there….

Maria: Isn’t it awesome? I invested in this company recently, you know, so… full disclosure I guess. But this VR setup is so great! It’s like we’re actually hanging out again!

Marquis: I was skeptical honestly but it does look pretty cool.

John: Totally. Hey sorry I had to schedule last time.

Maria: Yeah wait what happened? Gaby said you were in jail?

John: Yeah …. I got arrested at a protest.

Marquis: Wait really? No offense John but you’re not like, a protesting kind of guy?

John: [laughing a little] Yeah man, I totally wasn’t. But I found something I actually care about?

Maria: Cool! … are you going to tell us what it is?

John: Oh! Yeah sure, I mean, I just didn’t want to like, launch into some kind of lecture… but I mean… so I guess broadly it’s animal rights. But specifically animal testing. I got arrested because I locked myself to the door of Nicodemus’s main offices to protest their use of animals in medical testing.

Maria: Wait … but we have to test drugs on animals to make sure they’re safe for humans.

John: No we don’t.

Maria: What do you mean no we don’t… we wouldn’t have half the medicines we have now if we couldn’t test on animals.

John: That’s true, and in my opinion it’s an awful legacy we’ll look back on with shame.

Maria: I don’t think we should feel shame for curing people.

John: Do you think we should be allowed to test drugs on human inmates? You’re cool with the Tuskegee experiments?

Maria: [frustrated] No. Obviously not. But animals are not humans.

John: Would you be okay with Parker being used for experiments?

Maria: No, he’s a pet.

John: So what makes another dog different?

Maria: We have to make sacrifices, I mean, Gaby wouldn’t have her cool tattoo or any of her drugs without these tests.

Gaby: Hi there, I’m a human person not a bargaining chip to be used in an argument!

Maria: But you have to agree with me… right?

Gaby: I don’t know what I think, honestly. I’ve been reading about it since John told me he got arrested… it’s complicated.

Maria: There are already TONS of rules and regulations about what we can and can’t do with animals. You know I’m testing my eye drops on animals right John?

John: Yeah… I know…

Maria: And you think that’s wrong.

John: Yeah… I do. I wasn’t going to bring it up but… yes, I think it’s unethical.

Maria: There’s no other way. The FDA won’t approve something that isn’t tested on animal models first.

John: I just don’t think that’s good enough. Are these drops really worth torturing animals for? Sure, they’ll make you a whole lot of money, but I don’t think corporate interests should determine ethics.

Maria: I’m not a corporate interest John, I’m just one person trying to make the world better.

John: That’s what they all say.

[awkward pause]

Marquis [trying to change the subject]: So… I’m going to go next! I bought a house… here in Jacksonville. So if any of you ever want to come visit lovely Jacksonville, Florida, there is a guest room for you.

[silence]

Marquis: And I joined an intramural frisbee team, which is fun, although I am VERY out of shape. But it’s good to play a sport that nobody really cares about with other people who are way past their prime…. And it’s been good to meet new people. I’ve had kind of a hard time making new friends here in Jacksonville… even though I’ve been here… like five years now?

Gaby: Is your brother still there?

Marquis: No, after our parents died last year he moved back to Nashville. So it’s just me now. But work is here, and I travel a lot for that, so I feel like this is as good a place as any to buy? Besides, it’s a buyers market, so I got a great deal.

Gaby: Cool! I … honestly I can’t imagine a future in which I’m in Jacksonville… but if I am I’ll let you know?

Maquis: [laughing] yeah there’s… no real reason for you to come here/

Gaby: Travel is also hard for me anyway. Oh I got a new wheelchair! It’s really cool watch this, I can control the speed with my watch.

[light whirring noise]

John: Oh that’s cool!

Maria: [sarcastically] thank god it wasn’t tested on animals

Gaby: Come on Maria.

John: [frustrated] Okay I didn’t want to make this a whole thing

Maria: How could it not be a thing?! You think I’m evil!

John: Wow I definitely never said that.

Maria: Okay, unethical, you compared me to Tuskegee!

John: I did not, I asked you a question about your FEELINGS about Tuskegee I did not say you were the same thing.

Marquis: Can we maybe just like, not talk about this?

John: Sure.

Maria: You know what I have to go. I have a meeting.

Gaby: Maria come on.

[ding]

John: … I’m sorry I shouldn’t have brought it up. I didn’t think….

Gaby: It’s okay, I think she’s just really stressed.

Marquis: They got a big rejection from the FDA recently.

John: Oh man… I didn’t know that.

Marquis: Yeah, they thought it was a go, and the FDA sent them back to like, stage 2 I think? Which is going to cost the company a lot of money and… maybe like five more years?

John: Whoa. Maybe I should send her some flowers or something?

Gaby: That’s a good idea. She likes lilies best.

John: Okay, I’ll do that. I guess I should go too actually… but I’ll talk to you both soon?

Marquis: Yeah man, talk to you later.

Gaby: Bye!

[ding] [ding] [ding] [ding]

Rose: So, today’s episode is about animal testing. And before we go any further, I want to be super clear at the very beginning here, that this is a really complicated and controversial topic. I’m not going to be able to touch on every argument for and against animal testing. And you might hear some arguments in this episode that you don’t agree with. The goal here, my goal, is not really to convince you one way or the other, exactly. Instead, what I want to do is walk through what might happen if we did ban animal testing. What we could do without animals, and what we couldn’t. And what that decision might mean for people and animals around the world.

So at the end of this episode I am not going to say, here’s what we should do. Here’s what is right and just and good. I’m not even going to try to do that. Personally, I will just say right away that I’m still relatively conflicted about a lot of this stuff. I wasn’t sure exactly how I felt about the topic going into reporting today’s show, I hoped that maybe doing this episode would help me figure out where I land, but… it did not. I’m still not sure how I feel, having done all this research. So if you’re hoping that I’m going to have a solution for you, sorry… I’m not. Because there are no easy answers here, despite what some of the loudest people on either side might say about this stuff.

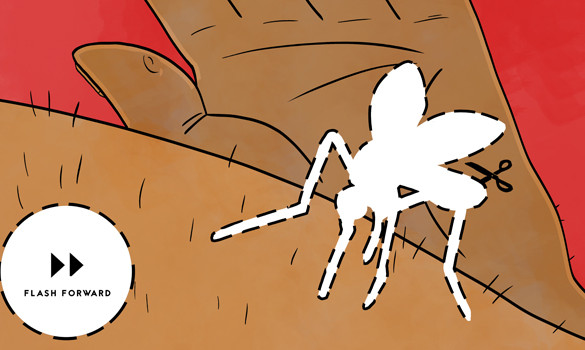

Okay, is that enough caveating? Let’s get into it. Animal testing. We do a lot of it. It’s actually hard to get numbers on exactly how many animals are used in experiments world wide. One study estimated that in 2005 that number was 115 million animals every year, but they also argued that this was probably an underestimate. For comparison, 115 million is about the population of the Philippines. It’s a lot of animals.

I think when most people think about animal testing they think about either cosmetics, where animals are used to make sure that a face cream or an eyeliner isn’t toxic or cause allergic reactions in people. Or they think of pharmaceutical testing where animals are used to test out the efficacy of new drugs. But those are not the only way animals are used.

Janet Stemwedel: There’s there’s a whole range of research with animals that isn’t any of those things, actually.

Rose: This is Janet Stemwedel, a professor of philosophy at San Jose State University.

Janet: There’s a lot of research that is research of non-human animals in their natural habitats, trying to understand, for example, how animal populations are responding to the stresses of a changing climate.

Rose: Animals are used in psychology studies, and neuroscience research to try and understand basic questions like how do neurons actually work. There are animal studies that ask questions about ecology and the environment, trying to understand the impact that humans have had on the world that we live in. These all fall under animal testing.

And this brings us to the first big question that we have to answer when we talk about animal testing. And this the question of why. Why do we test on animals? There are a few answers to that that question, which will pop up throughout this episode. But ultimately, we test on animals for two reasons: the first is that if we want to study animals we have to study… animals.

Janet: There’s some kinds of questions scientists want to answer that can only be answered with animals, because they’re questions about the animals themselves. Questions about how a particular kind of critter behaves, or how, you know, a particular kind of critter interacts with its environment

Rose: And the second reason, the one that’s more ethically murky, the one that we’re going to spend a lot more time talking about on this episode is that we test on animals because the tests we want to do wouldn’t be ethical to try on humans. The baseline promise of animal testing is that we can use animals to test stuff out that might be risky, that might not work at all, that might kill them, or cause pain and suffering. We use animals as stand-ins for humans in situations where we would not be okay with using humans.

Now, we did not always test drugs or cosmetics on non-human creatures. In 1937 a pharmaceutical company in the US created a drug they called “Elixir Sulfanilamide” to treat strep infections. This drug had a solvent in it called DEG, which is poisonous to most animals; humans and non-humans. But at the time, they didn’t know that, so they added some raspberry flavoring to the drug, and they sold it. Obviously, this did not go well, and it caused a mass poisoning in the United States. At least 100 people died across 15 different states. And the public was really mad, and for good reason, this drug had not been tested at all. At the time, there were basically no laws that required drug companies to do safety tests on new drugs.

The public outcry after this raspberry death drug scandal led to the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which requires safety testing of drugs on animals before they can be marketed.

In the US all animal experiments are monitored and approved by something called an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, or IACUC, which is a terrible acronym, but whatever. And Janet,who you heard earlier, serves on the IACUC for her university. And so here’s how it works, let’s say you are a researcher, and you want to do an experiment that involves animals. Before you can do that, you have to submit a proposal to the IACUC that oversees your work, and basically justify your experiment to them.

Janet: Tell us what the research is trying to find out. You know, what is the goal of the research, what is the aim? What is the the knowledge you’re trying to build, and why do you think that it matters to build that knowledge?

And, give us a detailed explanation of how many animals you need to use to get statistically significant results. Give us an accounting of what species of animals. Give us an accounting of exactly what procedures those animals are going to experience. What kinds of conditions the animals are going to be housed in between times that you’re doing the thing that the research calls for with the animals. Tell us what’s going to happen if things go worse than expected for the animal, in terms of pain and distress.

Rose: The first big thing that the IACUC wants to know is whether or not you need animals at all. As part of the application you have to show that you have done an extensive literature review to show that there is no other way to get the information that you’re trying to get, other than using animals.

They also look really closely at the number of animals you want to use.

Janet: How do I know that the number of animals I’m asking to work with is the smallest number I should be asking for permission to work with, that is likely to give me statistically significant results? So they can’t just make stuff up.

Rose: And of course they look at the animal welfare questions.

Janet: If there’s a way to do the procedures with anaesthesia, you need to do that. If there is a way to do the procedures not with anaesthesia, because the anesthesia would interfere with the thing you’re trying to measure, what kind of supportive care can you be giving the animal? How can you give the animal an environment where the animal feels the least stress, the least distress, and doesn’t have to suffer?

Rose: And sometimes the committee decides that the study just isn’t worth it.

Janet: The panel just looks at what’s being described as the benefit of building the knowledge, and compares that against the information we’ve been given about what the animal experiences, and we say for the benefit you’re describing with that knowledge, it seems like you’re putting the animals through too much.

Rose: And these IACUC committees don’t just exist at Universities. Private companies have to use them too. Now not everybody is convinced that IACUCs work, or provide a consistent level of scrutiny. In a study from 2001 some researchers looked into how reliable these reviews were. To do this, they took 32 different proposals and assigned them to two groups of IACUC reviewers. What they found is that 79% of the time the committees came back with different answers. Which suggests that not every IACUC committee has the same standards for things like animal welfare, or the necessity of a study.

Which, I mean, of course right? We’re talking about groups of humans being asked to evaluate and make decisions on things that are ultimately judgement calls. They are not always going to agree. And for some people, the idea of oversight and deciding which study is worth doing and which one isn’t, it’s all irrelevant. For some people, the idea of testing on animals is just wrong, period, and should be stopped.

Lawrence Carter Long: There are two major concerns, as I see it, with regard to animal experimentation. The first is that no animal — I don’t care if it’s a rat, a pig, a cat, a dog, or a primate — can consent to whatever that procedure may be, and most of the time those procedures end in death, because when they’re finished using the animal they’re not good to them anymore, so they toss them out. So the fact that animals cannot consent to the experiments, first and foremost, ethically, morally, says that we’ve got to find a better way.

Rose: This is Lawrence Carter Long, he’s the director of communications for the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund. And if his voice sounds familiar, that’s because he also played Kevin Macklin the inventor of ORYC on the cement episode last mini-season. Anyway, Lawrence has longn n been involved in animal right and protesting animal testing. And like he said he has two main concerns, the first being consent, which he talked about. And the second is that he doesn’t think it’s worth the money.

Lawrence: Every dollar that we spend on an animal study is a dollar that we’re not spending on direct care, treatment, or prevention. And so, if we’re getting limited results through animal studies, why are we doing it to begin with? Could we not benefit more people, and spend those limited resources more wisely, by focusing directly, specifically on the human needs that we know exist, and treatments that actually work.

Rose: So there are two main pieces to this argument, one is that animal tests are expensive and that there is limited money. So maybe that money should be spent on care for living patients, rather than chasing hypothetical future drugs. But the second piece of this is the one I want to dig into: which is that all this money is basically being wasted. Because animal models and animal tests do not give us reliable information about the human body.

Lawrence: Do you go to a veterinarian when you’re sick? Why not? You don’t because non-human animals cannot — not one animal, not ten animals, not a million animals, I don’t care about the species — substitute for getting real information about human beings

Kristie: Even the NIH has reported that about nintey six percent of drugs that are developed and are tested efficacious and safe through the animal tests that drug companies use, and move on to clinical trials; about ninety six percent of those fail either in clinical trials or once they come onto the market.

Rose: This is Kristie Sullivan, the vice president for research policy at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Kristie: So, that’s a huge waste of billions of dollars in drug development money that companies are putting in to develop new drugs, only to find them in the clinical stage or in the market stage not to be effective.

Rose: So I will say here, right off the bat, that The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine is a controversial organization. They believe that everybody should be vegan, and they’re opposed to all forms of animal research. And, in the past, they have made claims that are not scientifically accurate. I’m not going to get into some of this controversy around the organization here, but I want to be transparent about who they are and what they believe. And I called Kristie because The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine is one of the groups that argues these tests that we’re doing on animals are not t actually telling us anything useful.

Kristie: They don’t capture the complexity of the human experience. We eat different foods. We have different genetic backgrounds. We have different diseases, or life experiences, that could all affect the way that chemicals interact with our bodies.

Rose: And it’s true, most drugs do fail in clinical trial, for all kinds of reasons. This is actually a big topic in medicine right now, in general — researchers and companies are spending billions of dollars on these studies and they aren’t always getting useful results. And Kristie argues that the main reason this happens is because the animal models that these labs used to get to the clinical trial part, aren’t actually relevant to humans.

Kristie: We’re not just 70 kilogram rats.

Rose; And this goes both ways, humans aren’t relevant to some animals either. Aspirin, for example, works in humans but kills cats.

And you have probably seen this effect in action — how often do you see a headline that touts some amazing medical breakthrough in mice that… fades into obscurity, and you never hear about again, because it doesn’t work in humans. Researchers have been chasing cures for everything from cancer to Alzheimer’s and getting really promising results in mice, that just don’t seem to translate to us. And Krisite and Lawrence both argue that at some point we have to stop and look around and ask… is this worth it? Is there any reason to be killing all these mice if they’re not actually getting us closer to the cures that we think they will?

And here’s something that might surprise you, there are lots of people who do animal research, who kind of agree.

Deepak Kaushal: Many of these trials fail because animal models, that are being utilized, are imperfect. Rodents, mice, and rats are imperfect models of complex human diseases, including complex infectious diseases like malaria, TB. and HIV.

Rose: This is Deepak Kaushal, the Director of the Southwest National Primate Research Center at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute. And the diseases that he mentioned — Malaria, TB, HIV – those are disease that are complicated, that involve the whole body, and that don’t behave in mice the same way they do in humans. So in those cases, Deepak says that yeah, we probably should stop using mice.

Deepak: So in my opinion, they play a role. Those models have have utility, but when it comes to testing products with the aim of transitioning them into human beings, it is wasteful, at least in the case of complex diseases that don’t typically occur in rodents, to use those as models.

Rose: But this gets us into kind of a sticky situation, right? If we admit that mice are not good models for humans in many cases, we might then ask, well, what are good models for humans? And the best answer to that is non-human primates. Macaques are the most common species used, but labs also use marmosets, spider monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and a handful of others. But, I think that most of us, feel more conflicted about testing on monkeys than we do on mice. Deepak included.

Deepak: It’s absolutely right that even as a as a life scientist, as a biologist, I’d rather tests on mice than monkeys. I feel the same way. But we have… as scientists, we are driven by evidence, and we have evidence again and again that stuff that comes out of mice does not predict the human condition — at least the diseases that I study primarily — very well. And that stuff that comes out of macaques, and non-human primates does, to a larger extent. Not one hundred percent, but to a larger extent. So, to me, is it ethical to test everything in non-human primates? No. Because they are superior, more evolved species. But is it unethical to have millions of people die of conditions for which therapeutic and vaccine development can be done, by testing in a few hundred macaques? Probably to me that is more unethical. So that’s what drives me.

Rose: And here’s where we come to an ethical crossroads. In what cases is it worth using animals in experiments, which do kill them, for human gain, and in what cases is it not worth it? Deepak thinks there are cases where animal testing is necessary to save lives. Lawrence and Kristie disagree, fundamentally. Lawrence has cerebral palsey, which could, in theory, be served by animal models — there is some work suggesting that you can basically give macaques CP for research purposes. Which means that, in theory, Lawrence could benefit directly from animal research. But he doesn’t care, he still doesn’t think we should do it.

Lawrence: We’ve got to get beyond “what works for me is what we’re gonna do, and screw everybody else.” There are greater principles at play here. And if I were to forgo those, just to benefit myself, what I lose is much greater than anything that I could remotely gain physically.

Rose: So, like I said, I am not going to try and get deep on these ethical questions in this episode. I will link to books and sources in the blog post if you really want to dive into that side. What I want to do now is talk about the future I promised you at the top of the show. What happens if we ban animal research. What are the alternatives. What can we do and what can’t we do right now. All that and more after this quick break.

[BREAK]

Rose: Okay, so let’s say that we woke up, looked at our phones, and there was a news alert that said, “All Animal Testing Now Banned.” I’m going to hand wave at how this happened, I don’t know, maybe we are now ruled by a robot dictator who sympathized with animals being subjected to stuff against their will. Maybe the Boston Dynamics dog is now our supreme leader and is exacting revenge for all the time those researchers kicked it. Whatever it is… the point is that animal testing is now banned.

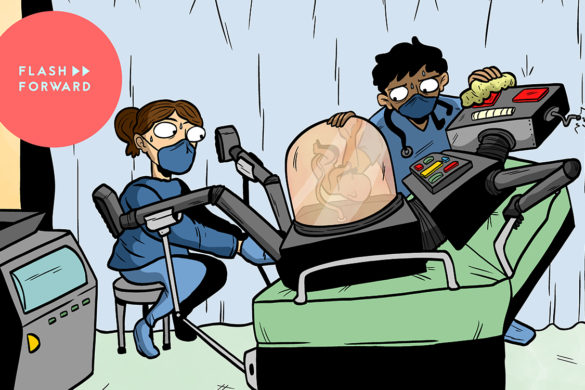

What happens next? Let’s start with what we can do without animals. One technology that’s in use right now, and that lots of biotech companies are working on is what’s called in vitro models.

Kristie: Right now, what we’re using in chemical testing are these really neat 3D tissues that are created with donated human skin cells, or keratinocytes grown up in a laboratory into a 3D version of our human skin.

Rose: Without these models cosmetics companies generally use rabbits. They’ll shave the rabbits hair off, and then apply the cosmetic to their skin to see what happens. With these in vitro methods, they can replace a lot of these tests.

Kristie: A laboratory can just put a cosmetic or a chemical on that skin, and see how it affects the skin.

Rose: And in the future, people hope that these kinds of in vitro models could be used to completely replace animals for cosmetic testing, where you really just need to know if the product causes irritation or a reaction to the skin or eyes. The challenge with in vitro tests is that usually they’re a single layer of cells in a petri dish. Which can be useful in some cases, but doesn’t represent a whole body right? If you’re worried that a mouse isn’t a good model for a whole human, a single layer of cells in a petri dish certainly isn’t either.

Hunter Rogers: There aren’t really any cells in the body that exist in that format. So you don’t really have two dimensional cells. It’s all three dimensional constructs. We’re not flat Stanley

Rose: This is Hunter Rogers, he’s a researcher at Northwestern University. And to try and solve this limitation of these single layer flat in vitro cultures, scientists like Hunter are working on a more complex system.

Kristie: One of the most exciting methods are what are collectively called micro physiological systems, or organs on chips. You can imagine a small silicone chip that is about the size of a USB sometimes.

Hunter: Typically when I describe its size, it’s about the size of an iPad mini. Maybe a little, a little smaller. Weighs a couple of pounds.

Rose: Organ on a chip! Maybe you’ve heard of this, it’s a technology that got a ton of hype around 2011ish. The idea that we could simulate a whole organ on a tiny little chip. Of course, the idea goes way further back than 2011, but that was around when the popular press picked up on the idea.

Hunter: So really what it comes down to is these organs on a chip are just technologies that allow us to recreate a tissue and organ down to the the essential functions of that tissue or organ.

So, for example, if you have a lung on a chip you want it to essentially be able to breathe, right? So you want it to be able to expand and contract, which is a similar thing if you’re creating a heart on a chip. You want the heart cells that you put into that system to be able to contract and pulse in the same way that you would see in a functioning heart.

Rose: These aren’t chips in the computer chip sense, by the way, they’re not digital. This is actual living tissue, usually cultured from a person’s actual cells. And because it’s more complex than that single layer of a single cell type, these organs on a chip are a lot harder keep alive. For example, in a living person,

Hunter: you have the circulatory system that has two of its major roles are distributing nutrients throughout the body and then eliminating waste.

Rose: In cell culture, you don’t have a circulatory system, really, you just have… cells. So in an organ on a chip system, you have to figure out how to get this waste stuff out and new nutrients in. And that’s something Hunter and his team worked on, and they actually kept their system alive for longer than anybody else, 28 whole days!

The other interesting thing that Hunter’s research team did was they actually linked up a bunch of different organs. So if we want a system that can replace an entire organism to test drugs on, we would need to build a whole human body on chips that talk to each other, right? That’s never been done, but what Hunter worked on was something called the EVATAR project.

And the EVATAR project attempted to recreate the female reproductive system on a series of connected chips. So they had a ovary, a fallopian tube, a uterus, a cervix, and a liver. Now you might be like, wait a minute, the liver is not part of the female reproductive system, but it kind of is. The Liver metabolizes a lot of the hormones produced by the ovary, so without it the system would get clogged up with those hormones, and it would mess it up.

Now let’s pause and clarify what the EVATAR system can and cannot do.

Hunter: When we first came out with the EVATAR paper, and there was a surge of media attention, there is a lot of headlines that we had created a robot that could menstruate. I mean just some really wild things that just were not true.

Rose: EVATAR is not a menstruating robot and it cannot actually develop an embryo so any questions of this system being used as an artificial womb are kind of out the window. But what EVATAR can do, is help researchers test drugs and treatments and see how they might impact the reproductive system.

Hunter: We’re currently working on developing a disease model for polycystic ovary syndrome. So this is a syndrome that affects you know anywhere between 1 and 5, 1 in 10 women of reproductive age. It’s a very complex syndrome, and involves not only the ovaries themselves, but includes a number of different other organ systems including the pancreas, the brain, the liver. And so you see all of these effects that you can’t reproduce in a standard in vitro environment. And then it’s a syndrome that doesn’t naturally occur in animals.

Rose: Using the EVATAR they can test out different therapies for PCOS, and see if they have an impact, before trying them on people. And the ultimate promise of the organ on a chip system is that not only could they use these to test out drug safety and treatments in general, they could actually build you a personal body on a chip system, for personal medical tests.

Hunter: So can you take stem cells from a patient; differentiate them into lung cells. heart cells, endometrial cells, something like that. Put them in these systems, and then test a certain treatment regimen on those cells to see how they respond.

Rose: This is all very, very cool. It’s also all still pretty early. There are teams all over the world working on these systems, but right now they couldn’t even link them up if they wanted to.

Hunter: The issue was when you set all of these researchers loose to develop their systems, we didn’t develop it with the intention of eventually merging all of them. So what came out of it was a lot of really elegant, and high tech models but we couldn’t integrate them. So you had stand alone heart models, stand alone lung models, etc.

Rose: This is sort of like in the episode we did about 3D printed organs, and how none of the teams working on this are using the same file format, and that actually makes it really hard for them to work together and collaborate and combine their work? This is sort of similar, all these teams developed really cool and effective systems to replicate the heart, and lungs, and bones, but they aren’t compatible with one another.

And even when they do connect , which they probably will at some point, Hunter isn’t sure they could ever fully replace animal models.

Hunter: As much as I would like it to be a replacement, I think it is just another step in the pipeline that could potentially lead to lower number of animals that are used in studies. But I don’t foresee it being a complete replacement of animals. At least not anywhere in the near future. As complex as we can make these systems, there’s still complexity that we just don’t fully comprehend.

Rose: Organ on a chip systems are like cartoons, they give us a sense of how the body might react, but they aren’t a whole body. And they’re also only a picture based on what we know. There’s still a lot we don’t know about how bodies work.

This kind of reminds me of a short story by Jorge Luis Borges called On Exactitude in Science. It’s literally one paragraph, and he wrote it in 1946, and it’s presented as an excerpt from a fictional book. I’m going to just read it to you since it’s so short, so here it is.

… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

The point of this story is that if you really want a perfect picture of something, you have to recreate the whole thing. Any map is a necessarily an abstraction, it leaves out details unless you want the map to be the size of the thing it is mapping. And in our case, any organ on a chip is going to be an abstraction, it’s not going to be exact. The question is how inexact is good enough when it comes to safety testing and medicine.

Right now, organs on chips aren’t something you can just buy from a medical supply company. So it’s not like every university or company that wants to replace some of their animal tests can just get these, and use them. That said, there is interest and excitement in these alternatives and they probably could replace some animal tests one day. When that one day might be, that’s harder to say. But depending on who you ask, a total ban on animal testing might be the thing that actually kicks people into gear on investing and improving these replacements.

But other people see this future, the one in which we’ve banned all animal testing, as a nightmare scenario.

Deepak: So what would happen is, for example, in Africa there is now — within five years — a second Ebola outbreak that’s going on in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And there have already been people that have come into the US, and have been infected. Five years ago there was this West African Ebola epidemic. Testing of agents that have proven to be effective, and have saved human lives and American lives of people infected with Ebola was only possible because of non-human primate models. If there is no animal testing, because of whatever reason, the next Ebola that happens; we may not have agents to test that would be effective against it.

Rose: That’s Deepak Kaushal again,

Deepak: If there was a bioterrorism attack, we would not have agents to test to protect against these. And I’m not even going after the fact that we have 10 million new cases of TB every year which we need to resolve. And a million people dying of AIDS every year, and 2 million people dying of malaria every year that we need to resolve.

Rose: And he’s obviously on the opposite side of Kristie and Lawrence here, he argues that if we couldn’t use animals for research, we would lose a key tool in the medical arsenal, and open ourselves up to a lot of risk.

Deepak: So we would be much less safer society if we did not have the ability to do to work with animals.

Rose: His argument is that removing animal testing basically presses a big red stop button on medical progress.

Janet: And for a lot of people maybe that’s fine.

Rose: That’s Janet Stemwedel again,

Janet: But for some people with exotic diseases, or diseases that we’ve only recently started researching, or things that we’ve only recently understood as diseases, like addictions of various sorts, we might be in a position where we have to tell those folks, “well sorry, biomedical science didn’t find the answers that would have been useful to you during the period where we had the tool of research with non-human animals available. So, you’re just gonna have to take one for the team.” And I think we need to think about that as a society; whether telling members of society who are not currently adequately served by our biomedical knowledge, “you all are the ones who should take one for the team.”

Rose: Deepak can point to medical treatments that were developed using animal models to argue that they’re necessary. Take Tuberculosis for example. The fact that TB is caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis was confirmed via animal tests. And the TB vaccine was developed in animal models.

Deepak Kaushal:There is no other way to do it, other than to infect humans, which is unethical.

Rose: Right now the TB vaccine, which is called BCG, works pretty well to prevent kids from getting TB, but it doesn’t work that well at preventing adults from getting it. The CDC says that in 2017, there were 1.3 million TB-related deaths worldwide, and one of the things that Deepak works on is developing a new TB vaccine.

Deepak: Vaccine candidates that are likely to replace BCG, as more effective TB vaccines, and therefore get rid of the scourge of TB, are being tested in animal models. And it is virtually impossible to identify which vaccines are likely to work in humans, and which are not, unless we use animal models. Particularly non-human primate based animal models.

Rose: On the other side people say, well, you might not have needed animals to figure out that that bacteria caused TB. Which is kind of impossible to test, since we can’t go back in time and see if they could have figured it out without animals, right? And it’s worth saying that just because we did something in the past doesn’t necessarily mean we should keep doing something now.

Lawrence: While it may be true that a fraction of animal experimentation may have been of some value to somebody, at some point in time, the issue today in 2019 is not whether all animal experimentation should be abolished. The important question is not: is some animal research necessary? But rather, are we wasting billions of dollars on inappropriate animal studies, and what else could we be spending those resources on?

Kristie: Even though we have put billions of dollars into research on Alzheimer’s disease, every single drug that’s made its clinical trials has failed because it’s not efficacious enough. So, I think we really need a paradigm shift and we need to see this realization that we have a responsibility to be more accurate in our prediction of health and disease, and finding treatments for those diseases.

Rose: The rift between these two opinions is hard to bridge with data. I think, annoyingly, that both of these things are probably true. Animal models are not as good as we want them to be, especially mice. But some things that we do in animal models do have a big impact on the human population and do make the world a safer place. There’s a study in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine from 2008 that both sides like to cite as evidence that their position is correct. This study tried to evaluate the claim that quote “virtually every medical achievement of the last century has depended directly or indirectly on research with animals.” And what the study found is that that is not true, it is not true that virtually every medical achievement has depended on animals. But it also found that quote “Animal models can and have provided many crucial insights that have led to major advancements in medicine and surgery.”

So if we couldn’t test on animals, we’d have to use other methods. And probably we’d wind up doing more testing directly on humans.

Janet: And my question then is: okay so which humans? Is it going to be how it too often has been in the history of research with human subjects, that the people who are taking the risks in those human studies are economically or politically marginalized people? And I see no sign in our current society that they wouldn’t be.

Rose: There’s a long history of human medical experimentation and ethics that we don’t have time to get into now, but it’s possible that in a world without animal testing we’d wind up incentivizing the wrong kinds of solutions.

Kristie: Food testing isn’t something we’ve really talked about, but some flavors, and other food additives are tested on animals. And maybe that’s something we can lose. We don’t really need the next flavor of Doritos. [2]

Rose: Blue is the best flavor of Doritos, just for the record. Also, the best flavor of Gatorade. Anyway, it’s also worth remembering that animal research happens beyond the walls of pharmaceutical labs and medical departments. Everybody studying animal behavior, physiology, psychology, all of that is out the window. All of the technology that we talked about in the last two episodes of this mini-season, is probably off the table. No more nanoparticle injections into the eyes of rats to give them night vision. No testing of potential biomarker dies to make sure they’re not toxic in humans. Animal research also includes veterinary research, testing drugs and procedures meant for animals.

Janet: So if your companion animal, your dog, your cat, your rabbit, your guinea, pig has a problem that veterinary medicine doesn’t yet have a solution for; well you’d better start making your plans to dig that hole in the backyard. Because your vet won’t be able to help a whole lot now.

Rose: Now, some animal rights activists don’t believe we should keep pets at all, so maybe this is a fine ripple effect for them. But Janet also worries about some of the basic science research that gets done on animals, and what ending those research programs might mean for those labs, and for investment in science in general.

Janet: If we’ve decided as a society that we’re happy standing pat with what we know right now, then maybe we don’t even need to fund so many scientists. Maybe we can cut back on the amount of funding we put into training new scientists.

Rose: Now, in Lawrence’s version of this future, that money is diverted to treatments and support for folks who are living with conditions now. But that’s not a given, right? We’d have to be really careful to make sure that that was what happened, and write that into the policies and laws, which isn’t impossible but would be tricky.

Ultimately, a lot of this comes down to tradeoffs. What are we willing to subject creatures to, and to what end? How confident should we be about our methods before we try something? And how much are we willing to risk giving up to make the world better for the non-human animals that we share the planet with? More and more research is revealing that animals have complex inner lives; that they know what’s going on around them; that they not only feel pain but also have conceptions of self, and long-term memory, and can experience trauma. How do we incorporate that information into these ethical questions and decisions?

I told you that at the end of this episode I wasn’t going to have an easy answer for you. And here we are, and I don’t. I’ll admit now, now that you’ve heard this whole thing, that I almost killed this episode several times. I almost decided to trash the whole thing and just … do something less complicated and less controversial. Less likely to result in hate mail in my inbox from either side… probably both sides honestly. But I kept coming back to something that Janet said when I talked to her.

Janet: It’s like, well… it’s like a lot of things; living in the world can be complicated, but I don’t think the fact that it’s complicated gets us out of doing it.

Rose: It’s easy for me to make episodes about pieces of technology, or space pirates, or fisheries. But if we ignore these harder, stickier questions, we’re shirking our duties, I think. We should be thinking about how to make the future better for everybody, and everything. And that means… sitting with these complicated questions and feeling uncomfortable and unsure and trying to find a way forward. I don’t have an answer for you, but I do think that we should be thinking about this stuff. Because the future is for all of us, animals included.

[music up]

That’s all for this future. For more reading about any of the stuff that I mentioned on the episode you can go to flashforwardpod.com, there will be a blog post to go with this episode, like every episode, and this one has a looooong list of links and books and resources you might want to check out.

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Maria is played by Cara Rose de Fabio. Marquis is played by Rotimi Agbabiaka who is debuting a new solo show called Manifesto on June 21st at the African American Arts and Culture Complex as part of the National Queer Arts Festival. I will link to more about that in the show notes. John is played by Keith Houston, you can find his voice acting work at keyvoicevo.com, or, if you’re in the Bay area and looking for some wild and weird karaoke fun, check out Roger Niner Karaoke at rogerniner.com. Fun fact I love karaoke, so, I will be going to one of Keith’s karaoke nights soon, and probably singing slash yelling You Oughta Know by Alanis Morissette. Gaby is played by Eler de Grey, whose work you can find at degrey.studio that’s d-e-g-r-e-y dot studio. Special thanks this episode to Adria Otte (AH-tee) and Molly Monihan at the Women’s Audio Mission, where all the intro scenes were recorded this season. Check out their work and mission at womensaudiomission.org.

Flash Forward is mainly supported by Patrons! If you like this show, and you want it to continue, the very best way to make that happen is by becoming a Patron. Even a dollar an episode really helps. You can find out more about that at patreon.com/flashforwardpod. And again, I’m doing a special promo. If you sign up between now and the 30th of June, I will mail you a surprise. If financial giving isn’t in the cards for you, the other great way to support the show is by heading to Apple Podcasts and leave us a nice review, or just tell your friends about us. The more people who listen, the easier it will be for me to get sponsors and grants to keep the show going.

If you want to suggest a future I should take on, send me a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. I love hearing your ideas! If you want to discuss this episode, or just the future in general, with other listeners, you can join the Flash Forward FB group! Just search Facebook for Flash Forward Podcast and ask to join. And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

Okay, that’s all for this future. Come back next time, and we’ll travel to a new one.

could cut

could cut

7 comments

Thank you for this balanced, thoughtful take on the animal research debate. We appreciate you including Dr. Deepak Kaushal with the Southwest National Primate Research Center.

Hi Rose. Thank you so much for this episode. It gave me a lot to think about! I honestly don’t know what to think overall of the topic; as you make clear in the episode, the topic is a complex one with no easy answers. Thank so again for your reasoned take. I hope this comment can do at least a little to balance out the hate that you fear will appear in your inbox! I love Flash Forward. Please keep up the awesome work!

So, Rose, have you intentionally made it impossible to download mp3 files containing your podcast?

If not, how does one go about getting mp3 files?

Thanks.

Hi Joe! You can download any episode by clicking on the “Share” option within the player and then clicking the little down arrow.

[…] BODIES: This Is Not A Test […]

[…] This Is Not A Test […]

[…] don’t know. There’s a classic Borges story called “On Exactitude in Science,” which I’ve referenced on the show before. It’s about mapmakers who try to make a really, really detailed map of the kingdom. And over […]