Today’s episode is about a future where nobody works on farms anymore, all farming is done by robots. Is it possible? Probably not. But it might be closer than you think.

Today’s episode features:

- Curtiz Marez, a professor at UC San Diego and the author of Farm Worker Futurism: Speculative Technologies of Resistance which is the book that inspired this episode.

- Sarah Mock, a former Wyoming farm kid turned farm researcher with the Farmers Business Network.

- JJ Price, the global marketing manager at Spread, a lettuce factory in Japan.

- My grandma. She doesn’t have a website.

We start this episode with some history, going back to the 1934 World Fair which featured the Farm Machinery Hall, full all kinds of machines: harvesters, threshers, cultivators ,corn pickers, mowers, tractors and mechanical cotton harvesters. There was even a milking machine on display, set up to milk an animatronic cow that could moo, switch its tail, turn its head, wink, chew cud and breathe. The cow was even rigged up with an internal set of tubes to make milk come out from the milker.

It’s easy to look at some of these future predictions from the 1930’s and laugh, but Professor Marez says that at the time there were some serious political undertones here. In the 1930’s, farm workers in California were largely migrants, and they were starting to organize and form unions and starting to demand rights and protections. At the same time, you started to have this moral panic, in California in particular, that the influx of Mexican workers stoked the racist fears of white families who thought that their women and children might be in danger. And this tension only got worse through the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s as workers rights movements got stronger.

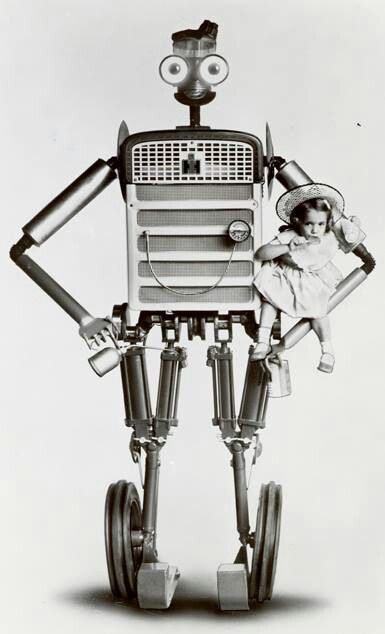

In response, some of these companies developed “farm bots” that they presented as mechanical alternatives to the so called “dangerous” Mexican men. In the 1930’s International Harvester Company sent a robot called “Harvey Harvester” to a variety of state fairs. Harvey looks crude today, but the idea was that he was a robot that could be controlled remotely by his master. I don’t think Harvey actually worked, but he was outfitted with a metal sombrero, and often photographed looking quite harmless next to pretty white girls. In the 1960’s Harvey got an upgrade and became Tracto the Talking Robot, and was often photographed holding white children.

In response, some of these companies developed “farm bots” that they presented as mechanical alternatives to the so called “dangerous” Mexican men. In the 1930’s International Harvester Company sent a robot called “Harvey Harvester” to a variety of state fairs. Harvey looks crude today, but the idea was that he was a robot that could be controlled remotely by his master. I don’t think Harvey actually worked, but he was outfitted with a metal sombrero, and often photographed looking quite harmless next to pretty white girls. In the 1960’s Harvey got an upgrade and became Tracto the Talking Robot, and was often photographed holding white children.

Another interesting thing about the 1930’s World Fair is that unlike a lot of the future predictions that it made, it was actually pretty spot on when it came to farming. Here’s some of what the ad for the company selling the radio controlled farm at the 1934 World’s Fair said:

“Will the farmer of the future be able to sit on his front porch while directing all his farm work? Will it be possible to sit in an office in Chicago or New York and direct the operation of fleets of tractors throughout the world? Will it be possible by these methods to operate farm properties in both hemispheres and gather harvests in practically every month of the year? These are a few of the unanswerable questions with which the weird spectacle of a driverless, yet perfectly controlled tractor, excites the imagination.”

Well, today these questions are answerable, and the answer is… yes. Sarah Mock explains that today, almost every farmer in the United States has a self-driving tractor. Farms are incredibly high tech, full of sensors and automation and millions of dollars worth of equipment.

Mock then explains that the future of farming could go one of two ways: bigger or smaller. Companies could, instead of dropping millions on a single huge piece of tech, deploy a hoard of smaller robots, each responsible for their own little patch of the farm. One company working on this kind of thing is called Rowbots,

Or, Mock says, things could go the opposite way and go huge. The USDA recently tested a gigantic sensor on a huge beam suspended over the farm that could scan and diagnose each plant.

And that 1930’s image of the command center, the farmer in his glass house orchestrating everything without stepping foot outside, that’s basically possible right now. Check out this John Deer commercial from the 2012.

But not every country has the kind of land that the US does, which means that some of the innovation in farming and automation doesn’t look like self-driving tractors. Instead, it looks like giant indoor farms like Spread.

Spread is a company that grows lettuce in highly controlled and highly automated indoor farms. Right now they’ve got one facility, and they’re working on building another. Recently, they got a lot of press about that new facility, which a ton of news outlets called the world’s first “robot run farm.” A lot of these stories claimed that Spread’s facility would be completely staffed by robots. That’s not true. There are still humans involved in planting, growing and harvesting this lettuce. Humans will plant the seeds, and put them into the rows at the beginning of the process. And humans will also harvest and trim and package the lettuce at the end of the process.

But Spread isn’t the solution for everything. They only grow lettuce, and as much as I love lettuce we’ll probably eat other things too in the future. Vertical automated farms aren’t going to be able to grow every kind of vegetable, and we haven’t even gotten into animals and animal products (assuming our future doesn’t wind up being a vegan one).

And our special guest this episode is my grandma, who tells us what it was like to be there when the milking machines first showed up on farms, and when tractors started replacing horses. She actually says that nobody really worried about being replaced by robots at the time, which was interesting to me.

We close out the episode with a conversation about a truly automated future, what would it be like if we really went full robot? We’ve got some sci-fi examples for this, but my favorite version is one that complicates the questions a little. It’s called Sleep Dealer and it’s a movie from 2008 about migrant workers, politics and robots. Here’s the trailer:

You can rent Sleep Dealer for a couple of bucks online, and I recommend it, it’s dark but really fascinating.

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth, and is part of the Boing Boing podcast family. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. Special thanks to Brent Rose for playing our tour guide. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky.

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! We have a Patreon page, where you can donate to the show. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next week and we’ll travel to a new one.

▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹

TRANSCRIPT

Rose: Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose and I’m your host. Before we go to the future, I want to tell you about a podcast that I really love called Gastropod. Gastropod is a show about food with a side of science and history and it’s so fascinating. Every episode co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley look at the hidden history and surprising science behind a different food or farming-related topic. If their names sound familiar that’s because I had them on this show last season! They talked about calories, and why you probably shouldn’t be counting them.

Later this month they’re doing an episodes on where modern restaurants come from, and on the history of veganism and vegetarianism and I’m sure they’ll be super interesting. If you want to be the person at your next dinner party who has a ton of fun facts about whatever is on the table, this is the podcast for you! And who doesn’t love fun facts? Nobody! So go check out Gastropod on whatever podcasting app you use.

Okay, now — to the future!! Let’s start this episode in the year 2047.

Museum Host: All right, everybody with tickets for the 12:30 tour, come on this way. Have your tickets out please, and have a seat. Any seat works, come on in.

[door closes]

Okay, welcome, this is the 12:30 Agriculture through the Ages tour, is everybody here for that? If you not, let me know now okay?

Great, so let’s get you comfortable in the headsets first, and then I’ll explain how this will work. So in front of each of you is a headset. Go ahead and put those on.

So for those of you who’ve never taken a VR tour before, you just place the set on the bridge of your nose and pull the strap around the back of your head. If at any point you start to feel motion sick, simply remove the headset and one of our assistants will bring you some water.

Okay, so in a few minutes your tour is going to start. Please stay in your seats, the tour is immersive but remember, it’s still virtual reality. You may be tempted to get up and walk around, but you’ll wind up bumping into each other, so please stay seated and keep your hands in your lap.

Okay? Great, let’s get started. Welcome to the Agriculture through the Ages tour! I’m Sophie, and I’ll be your guide.

It might be hard to believe, but for most of human history, humans actually farmed the land themselves by hand.

We’re going to start in the year 11,500 BCE, when farmers in China began farming rice. They then moved on to soy, mung and azuki beans.

Now let’s go to 13,000 BCE, when farmers in Mesopotamia domesticated pigs.

Let’s fast forward, and go to 4,000 BCE, when maize, a plant much like corn, was domesticated in Meosamerica.

All this time, humans were spending hours and hours of their days out in the fields, working the land using their own human power.

But let’s flash forward to the first industrial revolution. In 1720, using mostly human hands, farmers could gather 19 bushels of wheat per acre. By 1840, that number jumped to 30. That might not seem like much compared to what our mechanical farmers can do now, but at the time it was unprecedented!

Despite a constant march in progress, humans still worked on the land for centuries after that first industrial revolution. In the United States, in the late 20th century, there were still five million people living on farms. Let’s zoom in on one of those farms.

This is the Lars family farm. You can see on your right there’s a dirt road, which leads out to a wheat field. On the left you can see the goats and pigs they keep for the family. There’s Mr. Lars now! He’s off to check and see if it’s the right time to harvest the wheat. You see that tractor he’s driving? Soon, it will become a self-driving tractor.

Now of course, you would never see a human growing or producing food, it’s simply not efficient of safe. But for most of human history it was human strength that pulled food out of the ground.

Okay, let’s see how that transition happened, let’s skip ahead to the year 2025…

[fade out]

So today’s episode is about a future in which all farming is done by robots. There are no more farmers out in the fields getting their hands dirty, driving tractors, digging holes, pulling fruit off trees, rounding up cattle, it’s all done by robots and drones and self driving machines. And this is a future that people have been predicting for a long time. At least since the 1930’s.

Curtis Marez: You know the earliest example that I talk about is the 1933 34 World’s Fair which is called the was called the Century progress.

That’s Curtiz Marez, he’s a professor at UC San Diego and the author of this really interesting book called Farm Worker Futurism that was actually the inspiration for this episode.

Marez: So you know if anyone has ever seen you know getting the of this fair it’s really you know very much at the center of historical images about the future so all kinds of futuristic kinds of styles and images that we think of from the period really came from this World’s Fair in Chicago. And you know one of the main buildings there are displays was by an International Harvester Company which of course was making a farm farming the bullets and farming technology. And you know really the floor that are really felt like a kind of like the world of tomorrow exhibits at Disneyland.

Rose: The 1933 World’s Fair … In the Farm Machienery Hall there were all kinds of machines: harvesters, threshers, cultivators ,corn pickers, mowers, tractors and mechanical cotton harvesters. There was even a milking machine on display, set up to milk an animatronic cow that could moo, switch its tail, turn its head, wink, chew cud and breathe. The cow was even rigged up with an internal set of tubes to make milk come out from the milker.

Marez: But the biggest display was of a radio controlled tractor and they had this sort of mock up of a family farm and a factory I guess a little robot or Androidy creature who was the farmer sitting on the front porch doing nothing but with his voice, a recorded voice inside this little farmer robot he was actually controlling that tractor making its making it move around

Rose: A lot of this is kind of kitchy, in the way that 1930’s futurism tends to be, but Marez says that it’s also important to think about what was going on at the time.

Marez: So almost every kind of advance in in agribusiness technology that you see from the 30s through up through the 80s and 90s was really a response to labor strikes the farmer strikes and so a way to try and deal with. And let’s see what happens. [23.9]

Rose: In the 1930’s, farm workers in California were largely migrants, and they were starting to organize and form unions and starting to demand rights and protections. At the same time, you started to have this moral panic, in California in particular, that the influx of Mexican workers stoked the racist fears of white families who thought that their women and children might be in danger. And this tension only got worse through the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s as workers rights movements got stronger.

In response, some of these companies developed “farm bots” that they presented as mechanical alternatives to the so called “dangerous” Mexican men. In the 1930’s International Harvester Company sent a robot called “Harvey Harvester” to a variety of state fairs. Harvey looks crude today, but the idea was that he was a robot that could be controlled remotely by his master. I don’t think Harvey actually worked, but he was outfitted with a metal sombrero, and often photographed looking quite harmless next to pretty white girls. In the 1960’s Harvey got an upgrade and became Tracto the Talking Robot, and was often photographed holding white children.

Marez: So you know various times in U.S. history especially in the 30s and 40s Mexican workers were represented not only as potentially volatile as labor activists as radicals and as potential communists but also represented often as sexual threats. And so having the farm worker bot as a substitute was potentially a very reassuring image for a public who might be concerned about agribusiness industries bringing city workers into their into their neighborhoods and regions.

And so I think it made it fun it makes you wait it’s like you were saying from our perspective it seems kind of strange. OK. And that is true but it also seems to me that’s a trap isn’t that far removed from from the Terminator in the second show. Well you know we have examples of the cuddly happy little robot mole was killer but can be easily transformed into protective of you know parent-like figure or servant even.

Rose: And as funny as some of the 1930’s future of farming predictions might have seemed, they actually haven’t been totally off. Here’s some of what the ad for the company selling the radio controlled farm at the 1934 World’s Fair said:

“Will the farmer of the future be able to sit on his front porch while directing all his farm work? Will it be possible to sit in an office in Chicago or New York and direct the operation of fleets of tractors throughout the world? Will it be possible by these methods to operate farm properties in both hemispheres and gather harvests in practically every month of the year? These are a few of the unanswerable questions with which the weird spectacle of a driverless, yet perfectly controlled tractor, excites the imagination.”

Well, today these questions are answerable, and the answer is… yes.

Sarah Mock: So basically farming especially in the United States right now is super advanced like crazy advanced we I mean every part of it is technological there’s nothing that is that technology does not play a part of in farming.

That’s Sarah Mock:

Sarah: So I grew up on a farm in Wyoming. That kind of is where my Irish cultural history began and then I studied science technology and International Affairs at Georgetown with a focus on agricultural development and then the last couple of years I’ve spent in Silicon Valley and the Central Valley in California working for a couple of different startups in the Ag tech space and I’m currently a farm researcher at a company called farmer’s Business Network which is basically a dynamic Agard amik network that lets farmers share data on farming practices and products and methods so that they can basically have more information to make better decisions on their farms.

Rose: And Sarah says that whatever notion some of you might have of farming being this low-tech, boots on the ground kind of thing…

Sarah: middle aged men like have dirty hands and like get slowly out of trucks with their dogs at dawn and walk towards asylum.

Rose: That’s… not really what farming is like. Modern farmers in America are running incredibly high-tech operations.

Sarah: Self-driving tractors which have actually been around for a really long time probably about since the 90s or so so almost 30 years. Farmers like don’t really steer tractors anymore which is funny. They Yeah they’re all self-driving they use satellites to like it precisely kind of guide them through fields so that you can kind of maximize yield.

Rose: And when it comes to the future of automated farming, Sarah says there are two ways things could go, big or small. Right now, farm equipment is big.

Sarah: So there’s there’s like a movement that either basically you’re either getting were either going to get bigger or smaller. Right now farm equipment is really big That’s one of the things that drives consolidation in the industry is that like you could easily walk into like a John Deere dealership and drop a million dollars on just like a tractor in a combine like farm equipment is incredibly expensive and that just like the shear cost of it causes farmers to have to own a lot of land and farm a lot of land to distribute the costs over a lot of acres.

Rose: And there are companies working on making these gigantic, expensive piece of equipment way smaller and cheaper.

Sarah: Well what if we just make like little tiny autonomous tractors that all like you would have like a hoard or like a flock of autonomous tractors that would all farm like a very small area and then you could like you know like when one breaks you would fix one and they could each like individual little tractor with like deal with like a very small field and be able to deliver it exactly what it needs to be that like in California where water is a big deal be that water or or nutrients or like even like sunlight or like shade to be able to provide that on a very minute scale.

So there’s a couple of companies one of them is called the robots with the W. So it’s like our O.W. be OT. [laughs] Very clever. They are doing kind of like this small little autonomous robots and that would be that would be like they would be entirely autonomous because they’re like the size of like a dog. And so that’s kind of the one direction that would also involve. I’ve heard like theories about like there would be drones like that’s kind of the no people anymore kind of a tiny one. One version of the no people farming future

Rose: The other version is to go HUGE. Even bigger than the current equipment.

Sarah: So actually the USDA just built for a different type of research but I think there’s been experimentation with this kind of thing. On a on a wider scale. It’s it’s like a field scanner it’s literally like like two football fields long. And it’s like this giant thing that is like suspended from a beam and it like scans literally like plant by plant through the whole field everyday it like moves up and down the field and just like scans and and runs tests like evaluates what the plant needs and then can like respond to it on an individual level so basically as far as automation goes it’s kind of we’re either going to go big or go small.

Rose: And what about the 1930’s image of the command center, the farmer in his glass house orchestrating everything without stepping foot outside? Sarah says that’s… almost possible.

Sarah:Yeah. But yeah I think I think we’re actually like really close to something like that already. And I think we could actually like a very funny it’s not funny it’s supposed to be serious but I think it’s kind of funny. John dear John Dear video from last year that is like yeah it’s like a five minute like futurists. It’s like a guy who like his dining room table is like a black mirror that is like a basically a giant iPad and he like controls his whole farm from it’s like a very strange like video of like a guy waking up in the morning and then he like control his own farm from the kitchen table it’s very strange but.

Rose: The video is really fascinating, and I’ll put a link to it in the show notes and on flashforwardpod.com. And when we come back we’re going to go full steam into this future, and talk to someone who’s making it happen. Plus, a very special guest. But first, since we have not yet moved to a money-free society, let’s do some ads so I can get paid.

[[ADS]]

Rose: Okay, so this episode we’ve been talking about a future in which there are no more farmers working in the fields, everything is done by machines and automated, perhaps controlled by one person in their living room. Or in his big board room in the giant city of their choice. And most of what we’ve talked about so far has been based on farmers in the United States, where we have plenty of land to work with. But some of the most highly automated farming doesn’t come from America… it comes from places where space is really limited and companies have to maximize their output in tiny, tiny spaces. So let’s go to Japan and talk about lettuce.

Rose: Do you think you’d be able to tell in like a blind taste test. Which ones were spread lettuce and which ones were from a different place?

JJ Price: I can’t I can’t tell the difference between you know two other types of lettuce but I can I’m pretty good at knowing whether or not it’s our lettuce or some other person’s lettuce.

Rose: This is JJ Price, the global marketing manager at a company called Spread.

Rose: So what is the difference. Can you describe it to me?

JJ: Sure. So I’m originally from the United States on the East Coast. So you know most of the lettuce that come from the East Coast you know probably several days old and shipped from the west. So I never really had growing up and ever actually tasted you know what a fresh lettuce should taste like coming here. You know I had plenty of opportunities just to take flight as the day was harvested maybe a few minutes after it was harvested and you know really depends on the variety. But one thing that I noticed is which is that the crispness. It’s crunchy. So in Japan they prefer this type of fresh crunch when you bite into the lead. And that’s the first thing that I notice the taste is very good it’s on point.

Rose: Spread is a company that grows lettuce in highly controlled and highly automated indoor farms.

JJ: The company was established in 2006 and what we do right now is we run and manage plants factories which is a form of indoor agriculture or vertical farming where we grow lettuce inside of a completely closed controlled environment which we can go on to or sell mostly supermarkets right now. So the factory been operational since 2007.

Rose: Spread is currently working on opening a second bigger facility. This new indoor farm will be able to harvest 50,000 heads of lettuce a day, compared to the old building’s 21,000 heads, to sell in about 2,000 supermarkets all over Japan. And one of the ways that the company is boosting that production is by automating more of the process. Recently, they got a lot of press about that new facility, which a ton of outlets called the world’s first “robot run farm” — I’m doing little air finger quotes there. A lot of these stories claimed that Spread’s facility would be completely staffed by robots. But that’s not true. There are still humans involved in planting, growing and harvesting this lettuce.

JJ: So in the new facility seeding will still be done manually and then once the seeds have germinated and begun to grow that’s when the automation kicks in where they will be taken to the cultivation or growing area and then transplanted. And what I mean by transplanting is as lettuce grow bigger we have to kind of spaced out the lettuce and place them out a little bit or give them more room to grow as they get bigger. So for instance the first stage of the panel will be start. So the first panel will have let’s say 100 seeds on it. And as they grow larger they will have to remove the panels that are saying no more than all of that will be done automatically through automation. And once they are reaching the final stage of production or growing the panels will be transferred for harvesting and then once the harvesting process is finished Tuman come back in for the packaging and final trimming.

Rose: But there are some advantages to cutting a few more humans out of the process. The most obvious one being they don’t have to pay as many people.

JJ: So labor cost account for maybe 30 percent of our operations. So we wanted to try to reduce those costs. With automation we’re able to do to reduce the cost by about 50 percent.

Rose: But the new space can also now be laid out differently, because humans don’t have to move around in certain spaces.

JJ: So the actual cultivation area in the new facility and the current facility is roughly the same. And then the way that we’re increasing production is that through automation we’re able to set the stage more efficiently. So we won’t need to have for instance as wide of an aisle for a human to walk through to do any cultivation process we can kind of narrow those down. Also we’re improving the actual environmental control mainly the air control system and then also using LCD lighting so that we’re also going to be able to speed up the production cycle. So from seeding to harvest the old facility is on average about 42 days. And then in the new facility that should come down to between 30 to 35 the per cycle.

Rose: At Spread, total automation isn’t actually their main goal. And JJ doesn’t think this future of fully automated farms, the one that all these stories claim his company is actually currently operating, will happen. And he actually doesn’t think that should be the main goal here.

JJ: I don’t see traditional forms of agriculture going vanishing anytime soon. You know depends on the time scale here. Eventually you know things will probably be fully automated. You know several hundred or thousand years in the future. But if I look at the near future and currently in our lifetimes I still think that each form of agriculture. If it’s just growing outside greenhouses or plant factories I think depending on the situation each form has its own kind of merit and the merit. So in Japan for instance you know the island country. It’s very mountainous so there’s not too much arable land. Vertical farming or plant factories has little more value here. But if you let’s say if you’re in a country that’s very has a lot of arable land cheap labor. It may not make as much sense from a business standpoint to move in that direction. So I just think that plant factories are you know another solution to a whole lot of problems that we’ll be facing in the future.

Rose: So in Japan, where there’s simply not a ton of farmland, this kind of approach makes sense. But Spread only grows lettuce, and as much as I love lettuce we do have to eat other things. A lot of crops aren’t going to work in this kind of indoor plant factory thing. Which means that our future probably isn’t a world full of towers where all the food is grown by robots.

So what does the future look like? One of the big questions people always ask about automation in any field, is whether it’s going to take all the jobs. And it might. Spread specifically added farming to cut down on the number of people it had to employ. But Curtis Marez, the professor we heard from at the beginning, says that history actually doesn’t bear out the idea that increased automation on farms necessarily cuts down on the number of farm workers. Between 1940 and 1982 the total number of farm workers in California increased 233 percent. Instead of eliminating all the migrant workers it actually wound up boosting the farm industry and giving them MORE jobs.

And that makes Curtis kind of skeptical of just how much today’s automation is actually going to wind up eliminating farm workers too:

Marez: Yeah I think so. You know I think a lot to talk about how this industry can produce was bent on eliminating people from the workforce. You always did you were limited because it sounds kind of ominous. So it’s not that the workers are killed but you just wonder what what happens to workers of color. There. So you know there was this magical world of automation where where there are jobs where we’re no longer existed. I guess you take a slightly different tack because it comes with the kind of historical hindsight. I am skeptical because of the promise of automation being that she has been such a long standing wall and has never worked that way. So part of me imagines I was skeptical that ever worked that way in the world in which technology displaced workers were really exists.

Rose: And there’s another thing standing in the way of fully automating farming. Farmers love technology, they’re driven by efficiency and they’ve been early adopters of a lot of tech.

Sarah: like we are just getting excited now about self-driving cars like in the. In the consumer world. But farmers have had self-driving tractors since the 90s. So they think it’s like old news.

Rose: But farmers also don’t really want to give up certain things.

Sarah: Actually the biggest barrier to something like that is that farmers don’t want that. Which was like shocking to me. I spent a lot of time actually out in the field talking with farmers and I asked them about like you know what technology are you most excited for what. Case recently came out with a cab-less tractor this year like a tractor that it’s entirely self-driving There’s literally not a place for a person to sit. And you know I think a lot of farmers were like excited about it because farmers are. Basically a lot of them love them to death but they’re like 12 year old kids who just look like toys.

And so farmers were excited about it but like 90 percent of farmers I talked to about that their feedback was I mean it’s a cool piece of technology but I liked driving my tractor. Like I want to do that. I don’t want to sit in my office all day if I wanted to sit in my office all day behind a computer I would get a job in town like I work on a farm for a reason. So I think if anything the biggest barrier to kind of like a fully automated command center type farmers is farmers.

Rose: Sarah says that the real challenge for farmers these days isn’t automation, or whether or not they think they might be replaced by robots. It’s whether they think they can still make a living farming. And this isn’t a new struggle either. Last season I called up my grandma to ask her about farming for the episode on a future where meat is banned. And when we were talking, she told me some interesting things about growing up on a dairy farm in the 1930’s. Remember the animatronic cow I told you about, from the 1934 World’s Fair that was showing off the fancy shmancy milking machine. Well my grandma didn’t go to the fair, but she does remember milking machines showing up on the farm.

Doris: I remember when they were doing milk by hand. And then of course the milking machines came along and I remember when all the farm machinery was pulled by horses. So we had teams of workhorse and they were not saddle horses they were larger horses. And I got to actually get a simple job like doing controlling the horses that were pulling the wagons for the hay.

Rose: So when the machines came came in was that a big deal?

Doris: Milking machines. Oh yeah there were two brands in those days one. They were little round round buckets suspended from the animal’s midsection on the straps like a harness and then they were off. And then the other kind my dad had were called It was called the LaBelle and ever just the big can that sat down on the cement floor and you’re the brands and we had being young we had jobs. So one of the jobs was washing the equipment because with once you buy the equipment then you are going to have to keep it clean. Of course and then it was the advent of tractors when the horses were people would keep their beloved horses or some of them just because they were fabulous.

Rose: And when I asked her about whether people were scared of being replaced by robots, she said … no. It wasn’t really a choice. If you wanted to keep your farm, you had to get with the technology.

Doris: I don’t know. I think because things change when my father started farming it wasn’t so much it was in some ways easier I guess because maybe there wasn’t that much competition or what it was. It seemed like if you grew some thing you could sell it and you didn’t seem to have to worry about making a profit.

Sarah: I mean farming has always been highly technological even farmers that don’t necessarily like have a lot of technology are so highly scientific and agriculture is being like a world of small businesses is a world that is dominated by like a technology treadmill. Where if. I mean. GPS guided tractors were novel in the early 2000s and now if you don’t have one you’re probably going out of business. So they like farmers are like they have to be super technological super kind of like forward and they’re thinking progressive farmers just always do better because. You know price of lands of price of land is high. It’s incredibly competitive business. And. Yeah there’s just there’s too much at stake. Kind of like I mentioned like you know if you’re moving two or three million dollars worth of assets every year you. You can’t afford to be left behind. So they’re just there yeah there is an incredible amount of technology in agriculture already.

Rose: And in some ways, Sarah says that right now American farms might be as automated as they’re going to get.

Sarah: I’ve talked to farmers who say it would be easy and maybe not easy but possible to farm 1200 acres on the weekend. Like they farm twelve hundred acres of corn and soybeans in Illinois and do it entirely around a full time job. So it’s already like pretty. You know pretty automated it isn’t necessarily a full time job to even farm like a pretty significant amount of land or it requires like very minimal help. Most operations I know even large operations I know a 5000 acre farm in Montana that’s farmed entirely by a father and son. They don’t have any hired people. So it’s already like a pretty We’ve really streamlined the farm in the United States and part of that’s because literally farmers just don’t have the money to pay anyone. So they had to figure out how to do it on their own.

Rose: But what if we did take it further, if we did actually replace every farm worker with some kind of android robot thing. That might not be on the horizon, but it’s certainly something that science fiction has dealt with before. In Star Wars planets like Tattoine use droids in the fields, in William Gibson’s book Neuromancer there’s a robot gardening crab, and even beyond farming a lot of sci-fi worlds use droids to do hard, backbreaking work.

One of my favorite future of farming sci-fi pieces is a 2008 movie called Sleep Dealer, directed by Alex Rivera. The premise of the movie is that a wall has been built between the United States and Mexico, cutting migrant workers off from entering the United States. Those workers are replaced by robots, but instead of those robots being autonomous, they are controlled remotely by the workers who couldn’t cross the border to actually do the work. Here’s a clip from the trailer:

CLIIP

So in the movie the workers, instead of going to the fields in the US, go into these big warehouses in Tijuana and plug themselves into terminals where they control the robots that are doing the work across the border. It’s a really grim movie, but it also feels very realistic to me in terms of the ways that technology and the politics of migration intersect. You can rent it for a couple of bucks online at sleepdealer.com and I recommend it.

Rose: So what if we did have a world where we did remove all the farm workers?

Marez: Wow… You know I guess you know all of the resources we have are for thinking about that. The second is signs victual resources say that the world of difference is higher. It’s reproduced in different in a different way. So you know the classic in this regard is is Blade Runner. We’re where the replicas of our whole you know effectively slaves their Android slaves who have occupied in low level occupations or positions off world. And I think what is it. Harrison Ford Dehors chief and this is directly from the Navajo code. The Android skins were called “skins” which historically is a derogatory term for Mexicans. And so you know there’s a sense in that film that you know in a world in which you have replicants or androids or robots doing a lot of work that the kind of racialized ideas engendered ideas that had attached to manual workers of the human were attached to robots.

So so I guess maybe maybe one of the answers is it’s hard to know what that will look like because every time you try to imagine if it ends up looking a lot like the world. [2:03.4]

Rose: So… and I’ve always kind of wanted to say this on this show, THE FUTURE IS NOW.

That’s all for this episode. Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth, and is part of the Boing Boing podcast family. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. Special thanks to Brent Rose for playing our tour guide. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky.

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! We have a Patreon page, where you can donate to the show. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

4 comments

can’t find where to write to you but surely In the Year 2525 is a reference to the Zager and Evans song, yes?

[…] https://www.flashforwardpod.com/2017/01/03/old-macdonald-had-a-bot/ […]

Totally late to the game here as I’m binge-listening to the podcast, but I’m thinking the reference in this episode has to be the Lars farm mentioned at the beginning, a reference to Luke’s family’s farm in Star Wars.

[…] of agriculture vanishing anytime soon,” Spread global marketing manager JJ Price told the Flash Forward podcast. “Each form of agriculture has its merits and demerits. In Japan, for instance, it’s an […]