Today we travel to a future where everybody lives underground.

Guests:

- Dr. Brian Toon, an atmospheric scientist and professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

- Jason Wright, a tour guide and resident of Coober Pedy, Australia.

- Dr. Youqin Huang, a professor at Albany State University who studies housing and migration in China.

- Dr. Eun Hee Lee, an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham, Malaysia who’s researched the psychology of underground spaces.

- Finbarr Fallon, a designer and visual artist based in Singapore.

- Rob van Son, a researcher based in Singapore who leads the Digital Underground project.

- Dr. Michael Doyle, an assistant professor of architecture at Laval University.

- Julio Amezcua, an architect based in Mexico City.

Voice Actors:

- Mom: Ashley Kellem

- Ben: Brett Tubbs

- Adam: Aiya Islam

- Song by Shannon & Scott of Song Salad

Images of projects we mentioned on today’s episode:

the Photocatalytic Cave, photo by Jaime Navarro

the Photocatalytic Cave, photo by Jaime Navarro

the Photocatalytic Cave, photo by Jaime Navarro

A hotel room in Coober Pedy

A hotel room in Coober Pedy

The opal mining museum in Coober Pedy

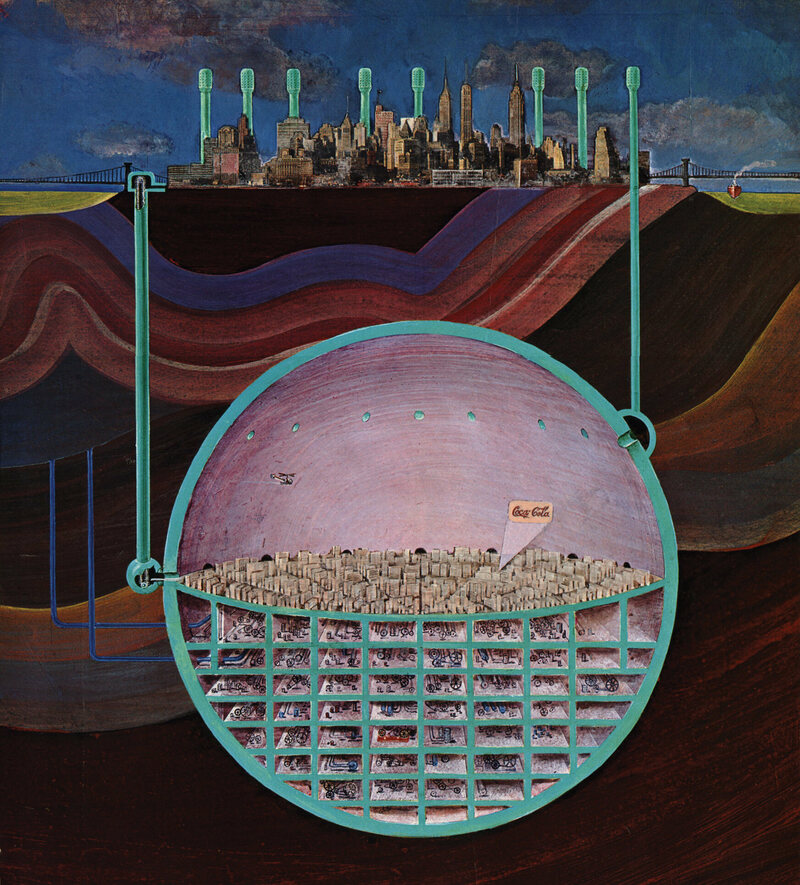

Oscar Newman’s Plan for an underground nuclear shelter.

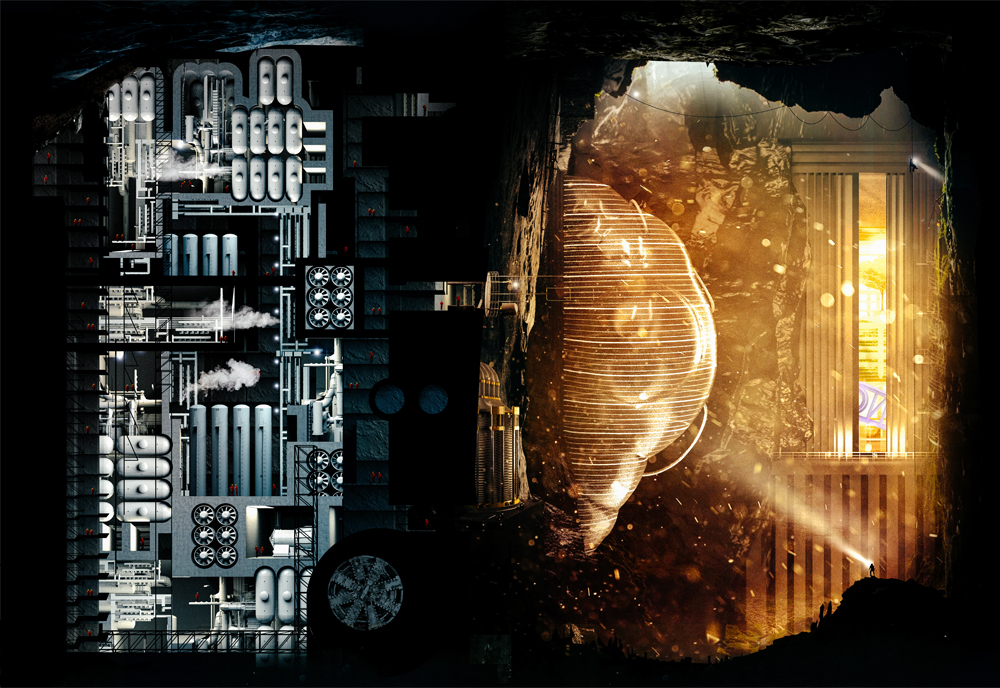

A still from Subterranean Singapore 2065

A still from Subterranean Singapore 2065

A still from Subterranean Singapore 2065

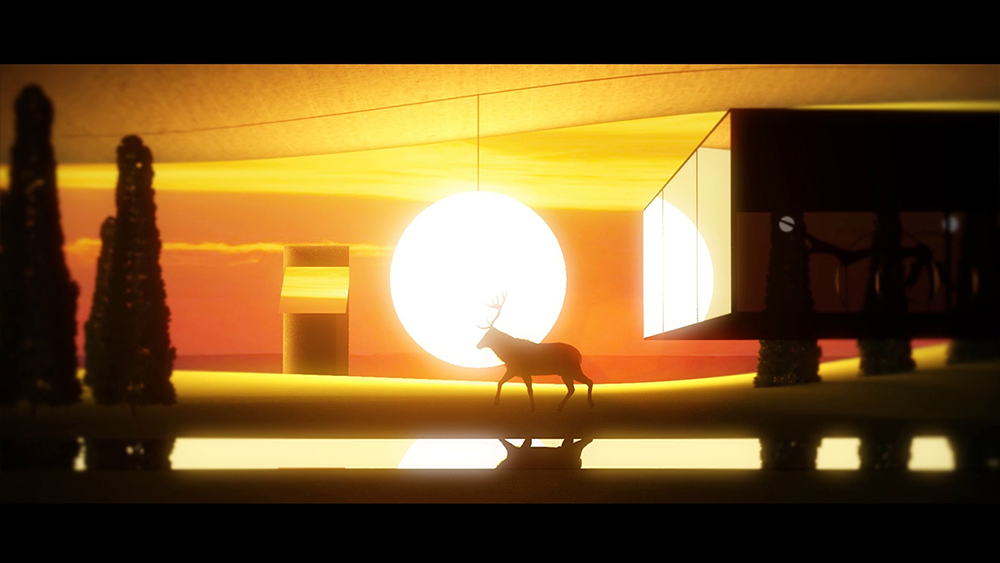

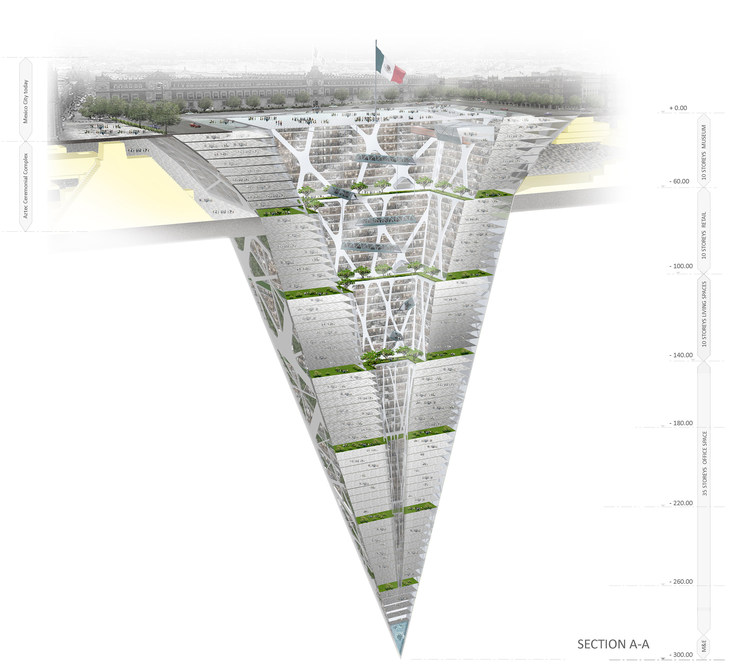

Earthscraper concept by BNKR

Further Reading:

- The deepest hole we have ever dug

- An Underground Elementary School That Doubled as an Advanced Cold War Fallout Shelter

- One Architect’s Spectacular Vision for a Spherical Subterranean City

- Nuclear Winter: Global Consequences of Multiple Nuclear Explosions

- How an India-Pakistan nuclear war could start—and have global consequences

- After the Bomb: Survivors of the Atomic Blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki Share Their Stories

- Earthscrapers: we may be living underground a few decades from now and not even miss the sun

- The climate crisis will make entire cities uninhabitable. It’s time to head underground

- Photos of Coober Pedy

- Derinkuyu Underground City

- Seattle Underground

- Rock-Hewn Churches in Ethiopia

- Invisible migrant enclaves in Chinese cities: Underground living in Beijing, China

- The extreme primacy of location: Beijing’s underground rental housing market

- The Caves of Forgotten Time

- 15 French volunteers leave cave after 40 days without daylight or clocks

- A Psychosocial Approach to Understanding Underground Spaces

- Digging deep: Singapore plans an underground future

- Subterranean Singapore 2065

- Sub/merged

- The Need for a Reliable Map of Utility Networks for Planning Underground Spaces

- Underground Potential for Urban Sustainability: Mapping Resources and Their Interactions with the Deep City Method

- Photocatalytic Cave / Amezcua

- Subsurface planning: Towards a common understanding of the subsurface as a multifunctional resource

- Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet, by Will Hunt

Episode Sponsors:

- Dipsea: An audio app full of short, sexy stories designed to turn you on. Get an extended 30 day free trial when you go to DipseaStories.com/flashforward.

- Memory Lane: From the writer behind the hit series Pretty Little Liars, Memory Lane is a psychological thriller about mothers, daughters, and the dangers of memory. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

- Shaker & Spoon: A subscription cocktail service that helps you learn how to make hand-crafted cocktails right at home. Get $20 off your first box at shakerandspoon.com/ffwd.

- Tab for a Cause: A browser extension that lets you raise money for charity while doing your thing online. Whenever you open a new tab, you’ll see a beautiful photo and a small ad. Part of that ad money goes toward a charity of your choice! Join team Advice For And From The future by signing up at tabforacause.org/flashforward.

- Tavour: Tavour is THE app for fans of beer, craft brews, and trying new and exciting labels. You sign up in the app and can choose the beers you’re interested in (including two new ones DAILY) adding to your own personalized crate. Use code: flashforward for $10 off after your first order of $25 or more.

- Purple Carrot: Purple Carrot is THE plant-based subscription meal kit that makes it easy to cook irresistible meals to fuel your body. Each week, choose from an expansive and delicious menu of dinners, lunches, breakfasts, and snacks! Get $30 off your first box by going to www.purplecarrot.com and entering code FLASH at checkout today! Purple Carrot, the easiest way to eat more plants!

Flash Forward is hosted by Rose Eveleth and produced by Julia Llinas Goodman. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. The voices from the future this episode were provided by

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹

FLASH FORWARD

S7E05 – “Could We All Live Underground?”

[Flash Forward intro music – “Whispering Through” by Asura, an electronic, rhythm-heavy piece]

ROSE EVELETH:

Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible… or not-so-possible future scenario. We always start with a little field trip into the future to check out what is going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to experts about how that world that we just heard might actually go down. Got it? Great!

This episode we are starting in the year 2095.

FICTION SKETCH BEGINS

[canned laughter applause]

MOM:

Kids! Breakfast!

[footsteps clomping into the room]

ADAM:

Don’t push me!

BEN:

Get out of my way!

ADAM:

Chill out!

BEN:

I hate looking at all this rock! Why does Adam get to have the room with the window?

ADAM:

It’s not even a real window! The view is just more rock!

BEN:

See? You don’t even appreciate it!

MOM:

Kids, please. No arguing before I’ve had my coffee.

Who wants some frosted potato flakes?

BEN:

Ugh! I hate having cereal for breakfast every morning.

ADAM:

Why do you even want my room? Your room is bigger anyway.

BEN:

Oh, so does that mean you’ll switch with me?

ADAM:

No!

BEN:

Mooooom!!

MOM:

Okay, okay, everybody calm down! You’ll get us kicked out of the cave owners’ association. You know the rules about noise in residential areas.

ADAM:

(quoting haughtily) “No unnecessary noises of a disruptive volume in residential areas before 9am or after 9pm.”

MOM:

That’s right. Now, Ben, you’ve always liked having the bigger room so you can do yoga in there. What’s going on?

BEN:

I hate yoga!

MOM:

You seem to hate a lot of things this morning.

[laugh track]

MOM:

What’s going on, honey?

BEN:

I’m bad at yoga.

MOM:

What?! You’re great at yoga!

ADAM:

Yeah, you’re better at it than me…and I’m not just saying that.

BEN:

Well, someone in my class said… They said that… They said I’ll never be really good at yoga because I have Seasonal Affective Disorder.

[audience “Awww…”]

MOM:

Oh, Ben. You know, nearly half the population has Seasonal Affective Disorder down here. It’s really very normal.

BEN:

Whatever.

ADAM:

Didn’t Stone Rodriguez have S.A.D.?

MOM:

You’re right, Adam. And they were one of the most famous yoga practitioners in Underground history!

ADAM:

I think Stone Rodriguez also got married at 18. You’d better get dating, Ben!

BEN:

(exasperated sigh)

[laugh track]

MOM:

Who said this to you, anyway?

BEN:

Jessica Li.

MOM:

Well, I’m going to have a talk with Jessica’s parents about this.

BEN:

Ohmygod no! Mom, don’t do that.

MOM:

Are you sure? I don’t like her talking to you that way.

BEN:

Don’t. I’ll handle it.

MOM:

All right, if you say so.

Well, I have to get to work. They’re opening that new tunnel on Left Side, and I need to be there early to help everyone find their way around. Don’t leave for school too late!

ADAM:

We won’t.

[Mom’s footsteps leaving the room, door slamming]

ADAM:

So… when you said you were going to “handle it” …?

BEN:

Got any ideas?

ADAM:

Stinkbomb her homeroom classroom, obviously!

BEN:

Augh! It’s going to last for weeks…

ADAM:

That’s the whole point!

[intro jingle starts]

THEME SONG:

It all started back in 1941,

When the U. S. of A. got to building that atomic bomb.

And said, “Whoopsie doo!” and dropped a few,

And some other countries built a couple too.

Oh no!!

For a while they paused the whole production,

‘Cuz of a pesky thing called Mutually Assured Destruction.

But that just couldn’t last and before too long,

In about the time it’s taking me to sing this song,

They had all moved down to Cave City.

Cave City!!

It was founded by a motley little band,

Mostly just whoever was on hand.

They all worked together and they pitched in,

They dug new homes and went spelunkin’.

Cave City wasn’t what they used to know,

They missed the sun, rain, and snow.

There was not much room and no fresh air.

Couldn’t feel the breeze of the wind in their hair.

Didn’t have that down in Cave City.

Cave City!!

Then a high schooler named Mary Brewer,

She volunteered to map the sewer.

She got put in charge of transportation,

And years went by without a vacation.

Then Mary grew up and had some children,

Who’d never seen the world she used to live in.

Never seen it!!

But they do their best and they get along grand,

And sometimes Aunt Rita comes by to lend a hand.

And they all live down in Cave City.

Cave City!!

Come join ‘em down…

Way down…

In Cave City!

FICTION SKETCH END

ROSE:

Okay, so today we are going underground. What if we all lived not up here on the surface, up where they walk, and talk, and play all day in the sun, but instead down below. Beneath the Earth.

[clip from Incredibles:]

“Behold! The Underminer! I am always beneath YOU, but nothing is beneath ME!”

How are people today thinking about how to build underground cities? Could we even live happily down there? Or would we all lose our marbles? And why would we dig down in the first place?

We’re going to talk about all of those questions on today’s episode, but let’s start with the last one first. What might drive humans to abandon our aboveground abodes and take residence inside the Earth? The first thing that Julia and I thought of here was a nuclear fallout. And in fact, there is a long history of countries building underground bunkers to prepare for nuclear war.

During the Cold War, while the Soviet Union and the United States were in a nuclear standoff, scientists from each country were, sort of, competing to see who could drill deeper into the Earth’s crust.

The deepest hole that humans have ever dug is more than 40,000 feet down. It’s called the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia. And 40,000 feet is basically the cruising altitude of a commercial aircraft, but down instead of up. And that might seem very, very deep, but it’s actually only about 0.2% of the way to the center of the Earth; fun fact. Locals today call this hole the “Well to Hell“ and claim that you can hear the screams of people being tortured in Hell down there from the whole, so that’s just very fun.

At the same time as this very, very deep hole was being dug in Russia, regular people started creating underground structures as safe havens in case of a nuclear apocalypse. There is the town of Artesia in New Mexico which built a whole elementary school underground. And in fact, students continued going to school there all the way up until 1995. In New York, there’s an architect named Oscar Newman who created an imaginary proposal for a bomb shelter that could house all of Manhattan.

You can find all kinds of cool… well, maybe not cool since it’s sort of about a nuclear apocalypse, but interesting to look at are proposals and diagrams for these kinds of bomb shelters and structures. And I’m going to post a bunch of them on the website and in the show notes and on the social pages this week for the episode. But the reality is that these kinds of bomb shelters aren’t exactly long-term solutions.

DR. BRIAN TOON:

It’sa lot of work to dig all those holes, not that many lava tubes and caves around, and actually putting people underground.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Brian Toon, a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder. And Brian was one of the authors on the original Nuclear Winter paper, back in 1983. But he did not get into studying the atmospheric effects of nuclear bombs because he was interested in global affairs or politics.

BRIAN:

Back in the 1980s, when I was a lot younger than I am now, I was investigating various things like, would exhaust from the space shuttle cause problems for the climate? And I also was studying the climates of Mars and other planets at the time. And so anyway, as part of this we thought about, “Well, what would happen if there were a nuclear war?”

ROSE:

So, I have a small confession for you, listener. I had totally heard of nuclear winter before, but before reporting out this episode, I actually didn’t really know what it was, specifically, or what caused it. Obviously, when a nuclear bomb goes off, there is that initial, direct impact. The bomb.

BRIAN:

So what happens when a nuclear weapon explodes? It’s like bringing a piece of the sun down to the Earth, and it creates a shockwave, and that’s what people mostly think about. And that’s all the military thinks about, is a blast wave that knocks over buildings and things.

ROSE:

Nuclear bombs are incredibly powerful. That’s kind of the whole thing of them. And they can and have decimated entire cities.

BRIAN:

That’s what atomic bombs are; they’re city killers. That’s what they’re designed to do. And that’s what they’ve been used for in the first nuclear war in 1945.

ROSE:

But these bombs don’t destroy cities just with the initial blast.

BRIAN:

Of course, there’s an initial fireball that everybody sees pictures of, nuclear weapons explosions. That’s something that lasts a very short period of time. There’s a lot of damage in the blast wave, but most of the damage area, which just looks like nothing but a pile of rubble, most of that damage is actually done by a big firestorm which was caused by this burst of light starting a fire.

ROSE:

And those fires are actually what cause nuclear winter.

BRIAN:

Now you have a hot bubble of air. It’s just like a balloon, except instead of being able to hold it in your hand, it’s as big as the city you live in. And that hot bubble of air is going to rise just like a balloon rises. So all the smoke that’s coming from this fire gets carried up into the upper atmosphere, into the place where airplanes fly. So what does the smoke do when it gets into the stratosphere and stays around for a long time? Well, the first thing it does is absorb a bunch of sunlight. So it gets dark at the ground.

ROSE:

In 2019, Brian worked on a paper that calculated what the impact of a “small” nuclear war would be on the climate. This paper focused on India and Pakistan. India and Pakistan have about 2% of the world’s nuclear arsenal between them. And if they deployed those bombs, the amount of death would be absolutely mind-boggling.

BRIAN:

If those two countries got into a small war, meaning between themselves, we’ve calculated the number of people who would get killed by the blast, somewhere between 50 and 120 million people.

ROSE:

To put that into context, in World War II, which is the deadliest war in human history, about 60 to 80 million people died. So this would be the highest death rate in a conflict Earth has ever seen. But that’s not the only impact that this “small” war would have.

BRIAN:

We predict that so much smoke would get into the stratosphere that it would lower temperatures on the Earth to colder temperatures than anything that’s happened in the last thousand years. Maybe some of your listeners have heard of the Little Ice Age. It would be colder than that.

Or maybe you’ve heard of The Year Without a Summer; it would be colder than that. So there would be frost and the growing season would be shortened. We’ve calculated that this would lead to a loss of food globally. That would be probably 30% or 40% of their yield.

ROSE:

This “little war” would not create global nuclear winter, but it could disturb the food supply of billions of people.

BRIAN:

So that was what would be happening after war between India and Pakistan. If you had a war between the United States and Russia, now you’re talking about 90% of the weapons on the planet. If they got into a war, you would have what’s called a nuclear winter. In that case, there’s so much smoke that like 80% of the sunlight is absorbed in the stratosphere, the ozone layer is destroyed, and it’s so cold in midlatitudes that you can’t grow anything.

ROSE:

So, nuclear bunkers were built in response to the threat of nuclear war, and they are there to protect you from that initial blast and then obviously the fires. And I had always thought that they would then protect you also from nuclear winter. But Brian says that once the fires are out, there’s kind of no reason to stay underground.

BRIAN:

The problem is food. It’s not really protecting yourself by being underground. It’s food. So there’s no real advantage to going underground, food-wise. You want to be going to the coast to try to catch a fish.

ROSE:

So these bunkers are not really, like, long-term solutions post-nuclear war, which I admit that I didn’t exactly realize. I guess I thought nuclear winter was more like a cloud of radioactive stuff that could still hurt you if you were outside. But no. That is not true. It’s that you would die of starvation and cold instead. Yay.

But beyond nuclear apocalypse, there are actually other reasons to dig down and build under the ground. Experts estimate that two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050. And a lot of those cities are constrained by space. New York City, San Francisco, Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, these cities don’t have a lot of room to grow. In other places, there are building codes that don’t allow for the city to expand in certain ways. You can’t build in Central Park without specific permission from the city, for example. In Mexico City, there are rules about what you can and cannot build in the historic city center.

So people have proposed going down to house all of these people that will be moving to cities. One architecture firm in Mexico City proposed a giant earthscraper, like a skyscraper but underneath the center of the city.

And then there’s the reality of climate change. In the mid-future, some places on Earth might get too hot to really be livable. And on top of that, there are the problems of air pollution, wildfires, and natural disasters. And in response, some people have argued that we might need to take shelter below the ground to make it through not a nuclear apocalypse, but more of a climate apocalypse.

Now, this is already the case in some places. There is a town in Australia, for example, called Coober Pedy, where more than half of the residents already live underground.

JASON WRIGHT:

It looks just like Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome because this is where it was filmed.

ROSE:

That’s Jason Wright. He’s a tour guide who’s lived in Coober Pedy for six years.

JASON:

It’s a strange little town. Most of what you see aboveground is junk because we live nearly a thousand k’s from civilization. We store all our stuff on the roof of our house, basically. (laughs) So yeah, there’s a lot of junk in everyone’s front yard.

ROSE:

Coober Pedy is north of Adelaide in South Australia, and about 100 years ago miners found opal deposits in the rocks there. But working and living in Coober Pedy is really tough. Aboveground, during the day, it can get up to about 120°F. Underground, however, it is more like 70°.

ROSE (on call):

What is it like living underground?

JASON:

Oh, that’s great. I wouldn’t have it any other way. There could be a nuclear war going on outside for a week here. And then of course, you have no light breaking up your sleep and no sound. It’s dead quiet under here. Yeah, it’s good.

ROSE (mono):

But Jason admits that he did not take to living underground immediately. It actually took him a while.

JASON:

When I first came to Coober Pedy back in 2007, I refused to stay underground. I used to roll my swag outside and sleep under the stars because I was a bit stressed about sleeping underground, but it grows on you after a while. You get used to it. And yeah, now I’d prefer to be underground than aboveground.

ROSE:

And it was even harder for his son.

JASON:

He’s now eight years old, and when we first moved here we couldn’t live on the ground because he just had a… There was no way. He’d sit at the front door of the dugout in the middle of the night crying, curled up in a ball. He just couldn’t handle it. But after about 12 months of him coming to work with Mom and Dad and spending time underground, he got used to it. And yeah, he’s the same as me now. He wouldn’t have it any other way. He loves living underground.

ROSE:

Other people fall in love with Coober Pedy immediately.

JASON:

We had an underground home about two years ago, and we took tourists through, and a family on the tour fell in love with it so much they offered to buy it and they ended up buying it off us. Yeah, after doing the tour they just said, “My God, we love your house. We want to buy it.” And it was within six weeks we were settled.

ROSE:

Again, I will post some pictures of Coober Pedy on the website and the social pages for you all to see because it really is an incredible-looking place. The homes are all carved into the earth like caves. And the walls are rock; they’re not finished out with drywall or anything. They’re not trying to pretend like they are not living underground.

Of course, I should say that underground living is not a new idea. Indigenous communities all over the world have built underground structures to live in or worship in for millennia. Indigenous people in Australia ventured underground to mine resources way before Coober Pedy existed. In Turkey, there is a huge underground city built around the 7th or 8th century BCE that goes 18 stories deep. Historians think it was designed to house 20,000 people in case the aboveground city was invaded.

There is something captivating about the underground for certain people. There’s something mysterious about it; this feeling that there might be things down there that we can’t even imagine. It’s sort of like the deep ocean, or outer space. But it’s also way more accessible to the average person. There are 17,000 caves in the United States alone, and way more tunnels, and mines, and catacombs all over the world. And you don’t necessarily need a lot of special equipment, or millions of dollars in research funding, to go down there.

I will say, asterisk there. Please be safe if you’re going to explore a cave. Go with an expert. Know what you’re doing. Don’t just go down there without having a plan.

And today, lots of cities have underground components or regions. Seattle was originally built at a lower level, and now there is a second underground city beneath the modern city. There are underground churches in Ethiopia. There’s the Oklahoma City Underground. Dallas and Houston both have tunnels for when it gets too hot to walk outside, while Montreal has them for when it gets too cold.

And lots and lots of people do live underground today, but it’s not always a good thing.

DR. YOUQIN HUANG:

China is in the process of what I call the urban revolution. Basically, very rapid urbanization process in the last few decades. So, hundreds of millions of people are leaving villages. They are leading farming and they are going to cities and engaging in industries and services.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Youqin Huang, a professor at Albany State University in New York. And in China, you can’t actually just move from the countryside into the city the way you can in most other places.

YOUQIN:

China, they have this unique system called a household responsibility system, which makes migrants, they can consider as outsiders illegal in cities. So they are not entitled to a lot of benefits, such as subsidized housing by the government and other benefits.

So in addition to this sort of massive influx of migrants into cities, there’s this market, you know, housing is expensive and so on, which happens elsewhere. But in China, there’s this policy. This institution makes it even harder for migrants to access affordable housing.

ROSE:

So what that means is that all of these people who are migrating to cities have to find places to live that they can afford in a system that is sort of built to exclude them. And a lot of those places are underground.

YOUQIN:

Usually they have very small space, and then you don’t have windows, you don’t have sunshine. There’s dampness and all that.

ROSE:

These tiny, underground apartments are the kind of thing that lots of people sort of know exist. In Beijing they call the folks living underground the “mouse tribe,” but Youqin says that most people don’t really know the extent of these apartments, just how many people live there.

YOUQIN:

I was in Beijing for a few months for my sabbatical quite a few years ago. So I rented an apartment outside of the university, which is a pretty expensive apartment complex. And at the end, I noticed this little entrance, and there’s, like, an ice cream cart there, and there’s people going in and out. And I was wondering, you know, “What’s that?” So I actually walked down the stairs. The stairs are very deep. There’s like two stories below and so on. So people actually live there.

ROSE:

But in 2012 the scale of this problem became a lot clearer.

YOUQIN:

There was a major storm, basically, in Beijing, and for whatever the reason, the drainage system wasn’t doing well, and also the rain was very heavy. So a lot of basements were flooded, and people were living in the basement, so people died from that flooding. And of course, then they have to be displaced and they come to the surface.

ROSE:

It’s hard to put a number on how many people live in these kinds of underground apartments in Beijing, or elsewhere in the world. I’ve read estimates that range from 150,000 to two million. And it’s not just Beijing, these underground communities exist all over the world. If you’ve seen the movie Parasite, these are the same kinds of underground apartments. And they exist outside of Asia. you can find them in New York City, for example, as well.

So what does this mean for our future? The big question that I think this raises is whether or not living underground is inherently worse, less desirable, less healthy than living aboveground or not. These underground spaces today are largely occupied by folks without access to resources or finances. They are places that are cheap and poorly designed and maintained. But does it have to be that way? Can living underground be as good or even better than living above? Or is it always a compromise?

We’re going to talk about that when we come back.

ADVERTISEMENT: DIPSEA

So, according to the internet, there’s a thing that’s about to happen, which is that lots of vaccinated and pent-up people are going to have a whole bunch of romantic fun this summer. Hot Vax Summer, they are calling it. And maybe you are like, “Yes. I am ready for this.” Or maybe you are like, “No thank you. I will stay inside my house still.”

Either way, Dipsea has something for you. Dipsea is an audio app full of short, sexy stories designed to turn you on. Each Dipsea story features characters that feel like real people and immersive scenarios so you feel like you are right there. Listen to stories about hooking up with your hometown crush that you never made a move on, or that co-worker you maybe always had a thing for. Or maybe a story that puts you in bed with someone who is telling you exactly what you want to hear.

Dipsea releases new content every week so there is always more to explore no matter what you are into or what turns you on. And Dipsea has a ton of variety and is really inclusive about sexuality, gender, size. There really is something for everybody. And if you are looking for a more, like, low-key wind-down, Dipsea also has wellness sessions, sensual bedtime stories, and soundscapes to help you relax before you drift off.

For listeners of Flash Forward, Dipsea is offering an extended 30-day free trial when you go to DipseaStories.com/FlashForward. That’s 30 full days of access for FREE when you go to DipseaStories.com/FlashForward.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ADVERTISEMENT: MEMORY LANE

If you like Flash Forward, you may enjoy a new podcast from Realm called Memory Lane. From the writers behind the hit series Pretty Little Liars, Memory Lane is a psychological thriller about mothers, daughters, and the dangers of memory.

If you like Black Mirror, Inception, or Blake Crouch’s Recursion, this is a great show for you. The story follows a daughter named Alex Bryant who asks her mother Cassie to participate in a study about implanted memories with her. But of course, things do not go according to plan. Both mother and daughter come out of the experience with weird dreams, flashes of places they’ve never visited, violent memories that they can’t figure out whether they’re real or fake. They are forced on the run from their own minds. And of course, Alex and Cassie have to trust one another like they have never before if they have any hope for survival.

You can listen to Memory Lane, available wherever you get your podcasts.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ROSE:

Okay, so today, again, plenty of people still go underground for work, for artistic and spiritual reasons, and all sorts of other purposes. But also, for many of us, the idea of being down there permanently is not super appealing. And this is the thing about the underground. It’s exciting, but also terrifying. It’s a place of limitless exploration, and cramped claustrophobia. It is associated with death and burial, but also with plant life and agriculture. So what exactly would it mean for humans to live underground?

It’s probably obvious, but it’s worth saying that humans were not designed to live underground. Human eyes are designed to see well when we have lots of light, but not so well as it gets darker. We also need sunlight to produce vitamin D, which helps keep everything from our bones to our immune systems working.

And it’s not just physical health. Living underground can also have psychological impacts. There are a whole bunch of weird and interesting studies about this, because it turns out there are actually a whole lot of reasons we might want to understand what would happen if we put people in a small, dark place for a long time. Everything from nuclear war to space travel, to submarines, to coal mining. And what these studies find is that people living underground wind up with wonky sleep cycles. Instead of our typical 24-hour pattern, our sense of a “day” gets longer, sometimes even up to 48 hours. In one experiment, the participant started sleeping for 30 hours at a time but said that he felt like he was taking short naps.

But it’s not all bad actually. Earlier this year, 15 volunteers spent 40 days underground together as part of an experiment on extreme living conditions. Most of them said they wanted to stay down there longer! Maybe they should move to Coober Pedy.

And beyond the perceptions of time, there are also other things happening to us when we spend time in an environment like a cave or an underground building.

DR. EUN HEE LEE:

The underground environment is a little unusual compared to the normal, like, aboveground space.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Eun Hee Lee, an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham, Malaysia. And Eun Hee researches the psychology of underground spaces.

EUN HEE:

Sometimes the physical environment can actually change the way your brain functions and that’s going to change the way your cognitive processes take place. So what I think is that the underground environment, the enclosed underground environment, is going to make this society more enclosed in general because it’s going to influence the way we think and behave among people.

ROSE:

Living underground is probably never going to feel exactly like living aboveground. And our bodies and brains are going to notice the shift.

EUN HEE:

For example, you don’t have windows, right? There’s no, like, direct access to the outdoor environment. So in that case, firstly, you’re not going to be able to see any kind of landmarks around you.

ROSE:

Research shows, for example, that underground, people have a harder time navigating. Maybe you have experienced this if you’ve ever gotten lost in a vast underground shopping mall or a parking garage.

EUN HEE:

So when people are in this kind of unusual, unfamiliar place, then again, they feel there’s a slightly higher anxiety associated with the space because they don’t know it; this is quite a new kind of place. When we are aboveground, we don’t feel like we are isolated. We are just there. But when you go underground, you’re going to feel isolated. So again, you know, the isolation, the feeling of that isolation is, of course, closely linked to the feeling of uncertainty.

ROSE:

That uncertainty can contribute to what Eun Hee calls “lack of perceived control,” which is basically what it sounds like. You are not necessarily panicking about being underground, but you also kind of have this subtle feeling like something is off. You feel disconnected from the usual ways you can control a space, like by opening a window. You don’t feel the same sense of control of yourself and your environment as you do aboveground.

EUN HEE:

So what would happen is when you have higher uncertainty associated with the environment around you, and when you in general feel that anxiety associated with it, then you can usually alleviate that kind of negative feeling through social cohesion, like a social support that you can get from the people around you.

ROSE:

In other words, when you’re feeling a little off-kilter, a little bit isolated, a little bit wary, you’re more likely to seek out other people and be more community-oriented.

EUN HEE:

What I actually can imagine happening with the underground community is that because of all these unusual characteristics around of that underground space, people are going to be probably a little more collectivistic in terms of the culture. So they’re going to bond with each other a little more because through doing that, through that social cohesion, they are going to be able to overcome all these negative feelings associated with it.

ROSE:

In the 1980s, researchers studying coal miners found that workers in the mines quickly developed solidarity and collectivism. Now, that wasn’t just because they were underground, they were also working in dangerous conditions, which we know can foster this kind of community too.

EUN HEE:

So I think all this evidence is kind of pointing towards this idea that maybe this underground social community will be a little more collectivistic in terms of the culture as opposed to individualistic.

ROSE:

This sounds kinda good, right? But at the same time, you don’t want people to be constantly uncomfortable underground, even if it does result in slightly more collective behavior. If we are really going to have a go at living underground in huge numbers, and we want that experience to be good, we’re going to need to figure out how to make these spaces feel, kind of, not underground.

EUN HEE:

I think this space can maybe have, for example, like a construction of lightwells or have skylights reaching. So if you have, like, a big lightwell in that underground space, then we will be able to see the skylight directly. I think that’s going to kind of increase people’s feelings of connection to the outdoors by letting that natural light come into the underground complex.

ROSE:

Eun Hee also suggested having a gradual descent, a kind of in-between space where you don’t feel like you’re just being plunged into a new, strange world. And they also said to make sure that everybody has plenty of access and ways to get to the surface.

EUN HEE:

That’s going to reduce people’s perceived barrier between underground and aboveground. So they are not going to be any more feeling isolated from the aboveground.

ROSE:

And there are more subtle things here too, like what we call these spaces.

EUN HEE:

Another thing I think we can do about these underground spaces is to not use the word underground. Maybe we should not even call it… You know, normally when we have these underground facilities, we would have ‘Basement Level One, Basement Level Two’. But instead of calling it that maybe… let’s say that this facility has something like Basement Level 10, even down to the 10, but we shouldn’t probably call it basement level 10. We should just call that Level One. And from there, it just builds up.

ROSE:

Remember that place in Mexico City where, instead of calling their design an underground skyscraper, they called it an earthscraper? That’s the kind of thing she’s talking about. Earthscraper does sound way cooler.

When you start reading up on the future of underground cities, underground construction, underground innovation, all roads pretty much lead to one place: Singapore.

EUN HEE:

Singapore, there is a problem of lack of space already. It’s a very packed city.

FINBARR FALLON:

Singapore, as an island, is tiny and it’s in a constant status of having a land crisis. It’s about half the size of London with almost six million people living here.

ROSE:

That’s Finbarr Fallon, a designer and artist based in Singapore who has explored ideas around living underground. And while lots of people have negative associations with the underground, Fin would actually love to live down there.

FIN:

I’ve always loved underground spaces and I spent a lot of time in caves crawling through tunnels in the UK and exploring these natural caverns. And I think they are fascinating spaces, certainly for exploration. And I always wondered through my studies in architecture just how we could manipulate such spaces to make them livable.

ROSE:

Over the past couple of years, Fin has made a couple of different pieces of art that explored ideas of underground spaces. The first was a short animated film called Subterranean Singapore 2065.

FIN:

Subterranean Singapore 2065 envisions a master plan for Singapore’s underground as a giant megastructure which spans beneath the central regions of Singapore and integrates a transport network together with vertically linked city, connecting the towers above with these promenade streetscapes which integrate many different functions such as reservoirs for collecting rainwater to underground parks, to office spaces.

[clip from Subterranean Singapore 2065:]

“Individual units are optimized for subterranean livability, incorporating inflatable technologies as well as lightwells and void spaces. Air from deeper underground reservoirs will be pumped in, naturally cooling the interior, therefore utilizing minimal energy.”

FIN:

So, one of the ideas for this underground master plan was to have this huge artificial sky which could mimic the qualities of light such that people within the spaces might not realize that they are in fact inhabiting underground spaces.

ROSE:

A few years later, Fin created a piece for the Singapore Art Museum called Sub/merged, which was a long installation showing a vast, master plan for an underground city.

FIN:

I envision these as, kind of, linear bodies, almost like promenades on a huge scale. You can have your own cavern and your own underground lake, and you could go sailing on your underground lake, which I think would be the most amazing thing. That’s my dream property, is to have a cavern beneath the city and a house in the rock.

ROSE (on call):

Would there be wind underground for you to sail with?

FIN:

So, you might have noticed in the film that there were flags blowing and other things moving in the wind, and there were these fans everywhere to create these artificial breezes which blow throughout these tunnel networks.

ROSE (mono):

These are all amazing ideas, and there is no shortage of incredible architectural renderings of these underground spaces. But whenever I see beautiful schematics of something like an underground city, I kind of wonder how realistic they are. Like, could you actually build that? Or is it a cool picture that would flood, or collapse under its own weight, or simply never make it past the permitting process in real life?

The realities of digging down, and building underground, are a lot more complicated than you might expect. And when we come back we’re going to talk about that, and what is actually feasible for our future underground spaces.

ADVERTISEMENT: THE SOUND AQUATIC

Hey, Rose here, and I want to tell you about a new podcast from some friends of mine over at Hakai Magazine. It’s called The Sound Aquatic, and here’s a little teaser.

[trailer for Sound Aquatic]

Hi, my name is Elin Kelsey. Early last year, I got together with my fellow podcast producers to start brainstorming a series all about ocean sounds. But just as we were getting started, a sound above the waves changed everything.

[news clip]

“It is now official. Canada has its first confirmed case of the new strain of coronavirus.”

We were making it in the midst of a globally significant moment for ocean research. A moment that came with quiet like we’ve rarely seen before. [cacophony of ocean sounds]

[upbeat music and ocean sounds in background] This spring, Hakai Magazine invites you to listen in on the extraordinary soundscapes scientists are recording under the waves, and to discover how the unexpected quiet of the Covid-19 pandemic is driving a new commitment to – shhh…

[music and ocean sounds abruptly cease]

– hushing ocean noise.

[upbeat music resumes]

Watch for episode one of our weekly five-part series coming out at the end of May. Find them all, plus exciting behind-the-scenes content and transcripts at HakaiMagazine.com/TheSoundAquatic, or search ‘The Sound Aquatic’ on your podcasting app.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ADVERTISEMENT: KNOWABLE

What do NBA All-Star Chris Paul, NASA commander Scott Kelly, and super smart podcaster Kristen Meinzer have in common? They all have incredible experiences, and they have taken those experiences and crafted audio courses to teach you what they have learned. Those audio courses are on Knowable, which is a new app where the world’s top experts teach new skills in bite-sized audio courses.

It’s sort of like someone took a podcast, added audiobook, and put them in, like, a pressure cooker, and then stood back and released that pressure with a totally normal and not-terrified facial expression, and what they got were little snippets of pure, distilled learning.

NASA commander Scott Kelly teaches lessons learned from a career in space. NBA All-Star Chris Paul discusses the performance benefits of his plant-based lifestyle. And podcaster Kristen Meinzer tells you everything she has learned about how to be happier from years of research.

Knowable is accessible on your phone and on the web, and each audio course is broken out into individual lessons, usually about 15 minutes long. You can explore at your own pace, and each class is supported by downloadable materials, lessons, recipes, and more. I know that you like learning, okay? You don’t have to lie to me. We are friends, sort of. And this is a place where learning is cool and good, and you can do it on Knowable.

So are you ready to learn something new today? You can download the Knowable app or visit Knowable.fyi and use the code FLASHFORWARD for an additional 20% off.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ROSE:

So Fin created this hypothetical proposal for Subterranean Singapore in 2016. But just a few years later, it actually kind of started to become reality. In 2019, Singapore released an underground master plan.

ROB VAN SON:

So, only recently… And I would say the release of the new master plan in 2019 was the main big signal that indicated this shift in how we look at land. So, land is scarce. We need to find more land or more space to meet the needs of the city, the city that is changing. The needs are growing. Instead of going outwards, we’re now looking downwards.

ROSE:

This is Rob van Son, a researcher also based in Singapore who works on a project called the Digital Underground.

ROB:

And what we’re really trying to help achieve is that better information, more accurate, more reliable information on what is where exactly within that underground.

ROSE:

Because here’s the thing about the land beneath our feet. It is not a blank canvas. There’s already a ton of stuff down there.

ROB:

In a city like Singapore, but in many other cities around the world, there’s already a lot of things going on on the ground in most cities. In most, like, modern developed places, many of the utilities are underground utilities; telco, water, gas, sewage, electricity, all those things that provide these types of services to the city.

ROSE:

And the older your city is, the more there is buried in the ground, and the more likely it is that those cables, and power lines, and tubes, and tanks aren’t super well mapped out.

ROB:

Don’t expect that to be very neatly organized. It can be extremely chaotic when you build aboveground. It’s often very tightly regulated. You cannot just build something that is different from how you proposed it to be. Someone will approve it, look at the design and assess whether that fits within the greater context. Underground, at least historically, development has been a lot more first-come-first-served, solve the problems as you go along. So, “Okay, there’s no space. There’s no space to build this new water pipe here. I’ll just go around a little bit, but I won’t tell anyone necessarily because no one is really interested in knowing that.”

ROSE:

One of the big goals of the Digital Underground project is to create a digital twin that represents all of the stuff under the ground. We’ve talked about digital twins on this show before, and in this context the idea is to have something that can change and update as the city grows and builds.

ROB:

So what we really hope is that this digital twin is alive. It’s a living map. It has its tentacles stretched out into the real world.

ROSE:

And it’s not just about buried infrastructure. It’s also about understanding that the earth below us is complicated.

DR. MICHAEL DOYLE:

The city has lived with its underground for a very long time. It’s kind of something that is, in a way, beneath its feet that is always somewhat unstable.

ROSE:

That’s Dr. Michael Doyle, Professor of Architecture at Laval University in Canada. One example of what can happen if you don’t have a great understanding of an underground space before you start digging, happened in 2005 in Lausanne, Switzerland.

MICHAEL:

During the construction of one of the metro lines in the city of Lausanne, they unexpectedly had the ground collapse in an important public space in the city.

ROSE:

Over 50 cubic meters of water and earth fell into this giant hole and formed a 30-foot gap.

MICHAEL:

And if you looked historically at this site, it was a place that was known to have a bog and the ground was very easily liquefied, easily going into a liquid state if the water content went to a certain level. This particular bog had been filled in, paved over for centuries. And it was only when they were digging underneath it that they suddenly, kind of, triggered this bog, this kind of soft ground.

ROSE:

Thankfully, nobody was killed, but it was a reminder that the Earth kind of has a memory.

MICHAEL:

Despite the fact that it doesn’t always resist to our feet, that the ground is not always so stable and that what we know about it isn’t so stable either.

ROSE:

Michael has spent some time working on a project called Deep City, which aims to better understand not just what we want to avoid when we dig, but what the resources down there might be so that we can use them in part of the planning.

MICHAEL:

What have we done there already? What has happened in terms of groundwater? What kinds of potentials are there for alternative renewable energy sources like geothermal energy?

ROSE:

The idea is that if humans are really serious about going down, about building huge underground portions of their cities, we’re going to want to do it in a way that actually works with what’s there, and not against it.

MICHAEL:

Are there materials that, when we excavate them, we don’t just send them to a landfill somewhere but can we use them as building materials? I mean, the idea would be to say we could build the building materials for the building from what we excavated from the site.

So, the Deep City Project was really kind of to say, “What is it that the ground kind of has already, or what is the ground’s potential? And then what do we do with that potential?”

ROSE:

Which kind of relates to this question of cost. It is really expensive to go down into the ground. Even tiny underground projects can cost a ton of money to create.

ROSE (on call):

What was the hardest part of this project?

JULIO AMEZCUA:

The budget. It was really small. It’s really small, but per square meter it was one of the most expensive projects I have done.

ROSE (mono):

This is Julio Amezcua, an architect based in Mexico City. And a few years ago, one of his clients came to him and said “Hey, I have this cave on my property and I want to do something really cool with it.” At first, he wanted to just do, like, a TV room for his kids.

JULIO:

So I came with him and then we went down to see the cave and he said, “You know, Julio, I want to do this type of place,” And I said, “You know, I think it’s too much effort and it’s too expensive just to for a TV room for your kids.”

ROSE:

So Julio proposed instead a kind of showroom for his client’s business. A place you can bring in potential buyers and really wow them. And the client was sold. It sounded amazing. But building something inside even a pre-existing cave is really hard.

JULIO:

First of all, because we have so much earth on top that could collapse. So imagine that you’re with your family at a party… Because it’s around 70 square meters and sometimes there’s a hundred people inside the cave. So imagine that thing collapsed. So the first thing was the structural.

ROSE:

The team used supporting columns and metal lintels, which are the same kind that you find in coal mines, to reinforce the space. They also installed a high-end air circulation system.

JULIO:

So there’s a lot of technological things going on there, you know, that you don’t see there. But it’s in order to… so you can be able to breathe, you can be able… to not collapse, and you’ll be able to be comfortable.

ROSE:

Then there were the more aesthetic design choices. And of course, Julio’s client only wanted the best.

JULIO:

So all the pieces, all the furniture, the lights, the materials, the very high-quality materials.

ROSE:

I have only seen this project, which is called the Photocatalytic Cave, in pictures, but I will say that it looks really cool. Again, I will post pictures of it on the website and social pages for the show. And Julio says that the cave achieved the thing that he always wants to achieve with any architectural project.

JULIO:

You know, I like to generate this effect of, “Wow.” I like when people come to a place and say, “Wow.” And I’m always trying to define what’s that wow effect.

ROSE:

And he says that when people come into this space, they definitely say, “Wow.”

JULIO:

So the people, they go down, down, down, and they go in, (gasp), and then they turn out the lights and they really catch your attention. And the response of the people is like, very “Come on, I feel like somewhere else.” “Where?” “I don’t know, but somewhere else.”

ROSE:

For Julio’s client, this was all worth it. But remember, this is the size of a studio apartment in New York City, and he already owned the house and the land. In other places, like Singapore, or Tokyo, or Shanghai, it’s way more complicated.

In some places, governments are incentivized to spend the money. Let’s go back to Singapore, for example:

FIN:

We have no land and we’re creating more land out of thin air. The value makes sense. And a lot of the developers here are actually given incentives by the government in terms of reduction in development charge to create links between their underground spaces.

ROSE:

In Singapore, the government owns a ton of the land in the city, and even land it doesn’t own it can build underneath, legally. But that’s not true everywhere. In Japan, for example, if you own the land, you own it all the way down to the center of the Earth. In other places, you can buy the mineral rights to land even if you don’t own the property above. This is very weird and legally complicated and we won’t get into it right now, but I am going to talk a little bit more about this on the bonus podcast this week.

You can really fall down a rabbit hole when trying to figure out how exactly this stuff could get built. There is a whole field, I have learned, of excavation research that I’ve been reading about, and that is really scratching my childhood obsession with construction equipment. But I will not bore you with that for now. Maybe on another episode.

But the thing that everybody I talked to about the architecture and design of these spaces said, is that they kind of require a new way of thinking about building.

ROB:

Typically when we think about land, we think about the maps that we look at, we look at it basically at a projection, at a two-dimensional projection of space. And it helps us make sense of that. It’s quite an easy perspective to most of us to work with. But underground space, I mean, going vertical, of course, requires you to look at space not just as a flat surface anymore, but instead you would have to look at it as a volume, as a three-dimensional space.

FIN:

We plan the city based on a 2D layout, a map. But I think what would be really interesting is to take this planning framework into three dimensions and say, “Perhaps we can start to play with the verticality of the city more.”

MICHAEL:

The way that we think two-dimensionally and plan means that we often think of what’s three-dimensional as being an extrusion from the plan towards the sky. And of course, we have kind of a historical relationship with building up towards the sky as a kind of metaphor for reaching the heavens, a metaphor for moving beyond our Earthly kind of existence as being almost something we try to escape from.

ROSE:

In the future, we’ll be seeking escape from lots of things, including the ways that we’ve altered the aboveground surface of the Earth.

FIN:

I think given the environment in which we live, I think the choice will come. Will the environment underground be more suitable for living in the future? Perhaps it might. The environment aboveground versus the environment below ground, would it be more pleasant to live in a different world rather than the world above? And I think it might be in the future.

MICHAEL:

There’s a strong interest in architecture for, kind of, an interiority; to be able to escape, in a way, the constraints that we started to realize climate was placing on us. And to be able to say we can escape into these artificial environments that allow us to, kind of, create the world as we see fit. And I think it kind of picked up on something we carried forward from the 19th century with the literature of Jules Verne and stuff with, you know, voyage to the center of the earth. The idea that into the ground we can find some sort of fantastical alternative existence for humanity, even discover one that we didn’t know existed yet.

ROSE:

In his book Underground, the author Will Hunt writes that when we’re lost:

Even our most deeply ingrained beliefs and thought lines may come undone as we open ourselves to new interpretations of reality. In the subterranean dark, we recover our capacity to be startled and confused and left in awe by the world. It reminds us that we are disorderly, irrational creatures, susceptible to magical thinking and flights of dreaming and bouts of lostness.

Maybe that sounds fun to you, maybe it sounds like a complete nightmare. Or maybe it sounds like just what humans need to reconsider what we have done to the aboveground parts of the Earth. Personally, I’m not totally sure I want to live in even the coolest cave there is. But then again, in the future, I might not have a choice.

[Flash Forward closing music begins – a snapping, synthy piece]

Flash Forward is hosted by me, Rose Eveleth, and produced by Julia Llinas Goodman. The intro music is by Asura and the outro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. The voices from the future in this episode were played by Aiya Islam, Ashley Kellem, and Brett Tubbs. The song you heard at the end of the sitcom scene is by the geniuses behind Song Salad. They also have a podcast, which you can listen to. I will link to it in the show notes. They were amazing to work with. I love having them on the show.

If you want to suggest a future that we should take on, send me a note on Twitter, Facebook, or by email at Info@FlashForwardPod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references that I’ve hidden in this episode, you can email us there too, Info@FlashForwardPod.com. If you are right, I will send you something cool.

And if you want to discuss this episode, some other episode, or just the future in general, you can join the Flash Forward Facebook group! Just search ‘Flash Forward Podcast’ on Facebook and ask to join. There is one question you have to answer. It’s very easy, just making sure you’re in the right place.

And if you want to support the show, there are a couple of ways you can do that too. Head to FlashForwardPod.com/Support for more about how to give and what you get in return; everything from a bonus podcast, to a newsletter, to a book club. If financial giving is not in the cards for you, you can head to Apple Podcasts and leave a nice review, or just tell your friend about the show. That really, really, does help.

Okay, that’s all for this future. Come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

[music fades out]