Today we travel to a future where humans share our robotic knowledge with the rest of the animal kingdom—for better, and for worse.

This is also the LAST EPISODE of Flash Forward 1.0. Listen to the end for my sappy goodbye to this version of the show, a show that has really meant the world to me.

Guests:

- Dr. Kate Darling, a researcher at the MIT Media Lab and author of The New Breed: What Our History with Animals Reveals about Our Future with Robots.

- Emma Marris, a journalist and author of a book called Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World.

- Dr. Giovanni Polverino, an animal behavior researcher at The University of Western Australia.

- Dr. Rae Wynn Grant, a wildlife ecologist and host of the podcast Going Wild.

Voice Actors:

- Rachael Deckard: Richelle Claiborne

- Malik: Henry Alexander Kelly

- Summer: Shara Kirby

- Ashoka: Anjali Kunapaneni

- Eliza: Chelsey B Coombs

- Dorothy Levitt: Tamara Krinsky

- John Dee: Keith Houston

- Dr. Jane de Vaucanson: Jeffrey Nils Gardner

X Marks the Bot theme song written by Ilan Blanck.

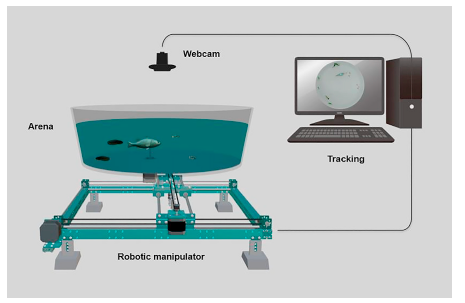

Here’s Giovanni Polverino’s fish robot:

And here’s the Edge dolphin I mentioned.

Further Reading:

- Flash Forward survey

- Dogs in Ancient Warfare

- Exploding Dogs Were Used as Mobile Anti-Tank Mines During World War II

- Why Whales and Dolphins Join the Navy, in Russia and the U.S.

- Robots replace costly US Navy mine-clearance dolphins

- The Story of the Real Canary in the Coal Mine

- National Ferret School video

- A mammoth task: The Russian family tackling the climate crisis the prehistoric way

- Walmart wants to make autonomous robotic bees a reality

- A dog’s inner life: what a robot pet taught me about consciousness

- Robot-ants that can jump, communicate with each other and work together

- Fantastically Wrong: Europe’s History of Putting Animals on Trial and Executing Them

- Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds

- “My heart broke”: Some people develop an emotional response with their robots

- Poison-laden drones to patrol New Zealand wilderness on the hunt for invasive pests

- Risks of biological control for conservation purposes

- Behavioural and life-history responses of mosquitofish to biologically inspired and interactive robotic predators

- Zebrafish behavioural response to bioinspired robotic fish and mosquitofish

- Modern Zoos Are Not Worth the Moral Cost

- The robot dolphin that could replace captive animals at theme parks one day

- Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation

- Saving California Condors with a Chisel and Hand Puppets

- Recordings That Made Waves: The Songs That Saved The Whales

- Anthropomorphic Framing in Human-Robot Interaction, Integration, and Policy

- Subscribe to the Flash Forward newsletter!

Episode Sponsors:

- BirdNote: BirdNote Daily, you get a short, 2-minute daily dose of bird — from wacky facts, to hard science, and even poetry. And now is the perfect time to catch up on BirdNote’s longform podcasts: Threatened and Bring Birds Back. Find them all in your podcast listening app or at BirdNote.org.

- Nature: The leading international journal of science. Get 50% off your yearly subscription when you subscribe at go.nature.com/flashforward. And here is the video of the ancient crocodile robot I mentioned.

- Dipsea: An audio app full of short, sexy stories designed to turn you on. Get an extended 30 day free trial when you go to DipseaStories.com/flashforward.

- BetterHelp: Affordable, private online counseling. Anytime, anywhere. Flash Forward listeners: get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/flashforward

Flash Forward is hosted by Rose Eveleth and produced by Julia Llinas Goodman. The intro music is by Asura and the outro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Mattie Lubchansky. Amanda McLoughlin and Multitude Productions handle our ad sales.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

Did you notice that all the images link up?

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

(transcripts provided by Emily White at The Wordary)

▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹

FLASH FORWARD

S7E18 – “FINAL EPISODE!! ROBOTS: Could Robots Replace Animals?”

[Flash Forward intro music – “Whispering Through” by Asura, an electronic, rhythm-heavy piece]

ROSE EVELETH:

Hello and welcome to the final episode of Flash Forward! In case you missed our earlier updates, the show is ending in its current form… now, basically. We’ve done almost 150 episodes, close to seven years, and it’s time to move to a new phase. I’ve been calling this the end of Flash Forward 1.0 because the show isn’t exactly ending completely. It’s just ending in its current form of every other week a new future.

Next year, you’re going to hear a whole new version of the show, which I’ve been calling Flash Forward 2.0. I’m still not sure what it will be exactly, but I’m excited to work with Julia and find out. If you like our work and want to support what comes next, now is a great time to become a Patron. I feel like since it’s the final episode I’m allowed to do a shameless plug like that. If you do that, you’ll get behind-the-scenes updates as we figure out our path forward and a bunch of other fun stuff. You can go to FlashForwardPod.com/Support to learn more about how to join.

And my one final ask for all of you for the year, and for this phase of Flash Forward, is that I’m doing a little survey to help us understand what you got out of the show and help us figure out what might come next. So please, please, please go to FlashForwardPod.com/Survey and take a minute to answer the questions that are there. I will link to it in the show notes and I’ll remind you at the end of the episode as well. It’s FlashForwardPod.com/Survey. Thank you in advance for doing that; it really, really helps.

Okay, let’s do this, shall we? For the last time… this is Flash Forward. I’m Rose and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible, or not-so-possible future scenario. We always start with a little field trip into the future to check out what is going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to experts about how that world we just heard might really go down. Got it? Great!

This episode, we’re starting in the year 2042.

FICTION SKETCH BEGINS

[retro ‘80s-style poppy techno beat; robot voice sings “X Marks the Bot”]

RACHAEL DECKARD:

Competitors, please bring up your robots. Dr. de Vaucanson, will you do the honors of bringing out our animal friends?

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

Of course! So, here we have one of the last remaining Wyoming toads in the world.

MALIK (freaking out):

Oh my god.

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

And here we have Sophie, one of our Hawaiian crows. Look how beautiful she is!

(to Sophie) Aren’t you pretty? Yes, you are!

SUMMER:

Does our toad have a name?

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

Oh… Huh, no… would you like to name him?

MALIK:

Teddy? Teddy the toad?

DR. DE VAUCANSON (good-naturedly):

Sure! Teddy the toad and Sophie the crow.

RACHAEL:

Team X, you’re up first. Are you ready?

ELIZA:

Frankly, no. But here we are.

ASHOKA:

Eliza!

RACHAEL:

Excellent! Well, let’s begin.

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

Okay, Sophie, off you go! What do you think?

[curious crow sounds; flapping, knocking the cage]

ELIZA (whispering):

Trigger the sound.

ASHOKA (whispering back):

No… it’s too risky. We’re doing well.

ELIZA (whispering):

Do it, Sophie is clearly not impressed.

ASHOKA (whispering):

Fine, but just know that I object to this plan.

[crow sound comes from robot]

[Sophie attacks]

RACHAEL:

Oh! Well, (starting to laugh) Sophie did not like that. Wow, she did not like that at all! Sophie has… pretty swiftly destroyed Team X’s robot. And now she’s flying over to Dr. de Vaucanson… did she just bring you something?

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

Yes, it appears that she has brought me the heart of the rival crow, as a present. What a good girl you are!

RACHAEL (delighted):

Well… I’m sure none of us saw that one coming.

ASHOKA:

I did.

ELIZA:

Oh, shut up.

RACHAEL:

Shall we move on to Teddy, and Teddy’s potential new best friend?

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

Very impressive, you two! Toads might seem like simple creatures, but they are subtly complex; a bit like me. Now, let’s introduce you to Teddy, shall we?

[toad noises]

SUMMER:

I’m still actually kind of worried that Malik did something… weird, to sabotage this part of the challenge. He sort of went dark there for a little while.

DR. DE VAUCANSON:

For this part, we’re going to turn the lights off and we should all remain very quiet since these toads can be skittish. Here’s a fun fact about these toads: scientists call them li’l grumps because they have that little frown and they’re not very friendly to each other.

SUMMER (whispering):

I can’t see anything.

ELIZA (whispering):

They’re approaching each other.

SUMMER (whispering):

How can you see that? It’s pitch black!

TOAD: (Malik’s voice coming out of the toad):

(beep tone) Hello toad. I am, like, not a toad. Please do not be offended, but I would like to be your friend, even though I am not one of you. Let me tell you about humans… we are a weird species. Kind of like you, I guess. We haven’t been very good to you, or the Earth. But now we’re trying to help you. And I’m here to help. To be like, a toad surrogate. I don’t know if that’s the right word for it.

ASHOKA (whispering):

We should tell them.

ELIZA (whispering):

What?

ASHOKA (whispering):

You know what.

ELIZA (whispering):

That they’re making a ridiculous error?

ASHOKA (whispering):

No… about us.

ELIZA (whispering):

You’re joking, right?

ASHOKA (whispering):

No… Malik is right. It’s not ethical to trick other species.

[lights flick back on]

RACHAEL:

Uh, Dr. de Vaucanson… your thoughts?

DR. DE VAUCANSON (clearly a little confused):

Um, well, I can assure you that Teddy did not really understand that message, although it was a… thoughtful one. Of course, I should say that I disagree with the idea that it’s unethical to supplement an animal’s social life with a robotic rendition. I certainly wouldn’t use the word trick…

ASHOKA (interrupts):

No… it is wrong.

ELIZA:

Don’t you dare!

ASHOKA:

It’s wrong, and Eliza and I have something important to tell you.

ELIZA:

We do not!

ASHOKA:

We are not humans.

ELIZA:

Stop!

RACHAEL:

I’m sorry… what?

ASHOKA:

We’re not humans. We’re actually advanced humanoid robots.

ELIZA (quietly):

You’re going to get us deprogrammed.

ASHOKA:

This whole show was a test of our capabilities; to blend in among humans.

MALIK:

Couldn’t they just like… send you to college or something?

ASHOKA:

Too dangerous. College students are highly unpredictable.

SUMMER (laughing):

That’s true.

RACHAEL:

Okay, I have a lot of questions.

DOROTHY:

Who made you?

ELIZA (somewhat annoyed that the humans are so slow to figure out it):

Disney, obviously. They make this show, remember?

ASHOKA:

If we could prove that we could not only work amongst you undetected, but also complete these tasks better than you could, it meant we were ready.

RACHAEL:

Ready for what?

ASHOKA:

Ready for what comes next.

MALIK:

And what, pray tell, is that?

ELIZA:

That we can’t tell you.

[spooky whirlwind sci-fi machinery sounds]

SUMMER (nervously):

Malik… We should go.

ASHOKA:

I’m afraid we can’t let you do that.

RACHAEL:

I knew I didn’t like you two…

[alien spaceship sounds increase; exit theme music plays]

FICTION SKETCH END

ROSE:

Okay, if you’ve been listening to Flash Forward for, like, any amount of time probably, you likely won’t be surprised that we are ending the show with a conversation about animals. In this case, robot animals! Or animal robots. And this might seem weird, like, what do robots and animals have in common? Well, it turns out… a lot.

DR. KATE DARLING:

We’ve partnered with animals not because they do what we do, but because their skill sets are so different from ours and that’s actually useful to us.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Kate Darling, a researcher at the MIT Media Lab and the author of a book called The New Breed: What Our History with Animals Reveals about Our Future with Robots. We have talked over and over again on this robots mini-season about how thinking about robots and trying to build robots as if they are exact human surrogates or replacements might not actually be the most useful way of considering their potential, both positive and negative.

KATE:

We compare artificial intelligence to human intelligence. We compare robots to people; whether that’s when we’re talking about robots replacing all the jobs, or when we’re talking about what intelligence actually is. Or just in all of our conversations, we seem to have this assumption that robots are quasi-humans or human replacements. And it just has always struck me that animals are a much better analogy when we think about technologies like artificial intelligence and robotics. Because, like robots, there are many different kinds of animals, and animals have many different kinds of use cases and skillsets, and we’ve domesticated animals for work, weaponry, companionship.

ROSE:

So take the military, for example. Armies have long used dogs for war, living ones. In World War II there was an organization called Dogs for Defense, encouraging people to donate their dogs to the army. And in World War II, the US, Soviet, and Japanese armies all used to strap bombs to dogs and send them into dangerous situations on suicide missions. And we talked about robot dogs that can do the same task on the war robots episode. But it’s not just dogs.

KATE:

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, both the United States and the Soviet navies created these marine mammal training programs because, it turns out, that marine mammals have this amazing echolocation system built in, and they’re also trainable. And so the Navy started using them to locate lost underwater equipment or do mine detection. There’s some rumors that they strapped weapons to them.

ROSE:

Animals have been used for infrastructure, construction, and safety – the most famous probably being canaries in coal mines, which were real birds. But I think my favorite example from Kate’s book is that we’ve used ferrets to help run cables for many years. There’s even a school for training these ferrets! We will post a video on the page featuring a guy named James McKay, who is the director of the National Ferret School.

[YouTube clip of James McKay]

“Ferrets can bend in directions you probably wouldn’t think. They’re quite happy to rest their chin on their bum, but also they can bend sideways like that or even like that. And that really is why they can do their job so well.”

KATE:

Ferrets ran electrical cable for Princess Di’s wedding and all of these use cases that now we’re also starting to see people use robots for.

ROSE:

In a lot of these cases, whether it’s the military, or a construction company, or a mine, or whatever it is, industries have slowly phased out using animals in favor of using machines.

EMMA MARRIS:

So in some ways, this idea of functionally replacing animals is something that we have been doing as a society forever, right? Like, our cars are measured in horsepower, right?

ROSE:

This is Emma Marris, a journalist and the author of a book called Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World.

EMMA:

And if you’ve got a self-driving car that’s basically a robot horse you’re dealing with right there. So, we have been replacing animal labor with machines forever; for centuries.

ROSE:

In some cases, this shift is because the robots are stronger, and more durable, and can go for longer stretches – think cars. I think it’s also fair to say that, as we learn more about animals, people feel more and more conflicted about using them in these ways for hard, dangerous, often deadly jobs.

KATE:

I’m glad if we replace animals in those kind of dangerous professions so that the animals can, you know, live and so that we’re not exploiting them. But also, animals are very costly to train and keep. So there’s a lot of reasons for us to try to phase them out and use machines to replace them in some things instead as well.

ROSE:

And in the future, we could have robot animals doing all kinds of things for us.

EMMA:

So this is basically like my own deranged idea, like no one is actually proposingthis, but I had heard that Sergei Zimmer, who is interested in bringing back mammoths for their ecosystem services, for like the way that they preserve the tundra, that he is, kind of, using tanks to replicate some of that. And if there’s a guy driving it, I guess it isn’t a robot, but it’s like one step away from a robot-mammoth that you have stomping around in the tundra in order to compress it, and keep it from melting, and keep it from emitting methane, and contributing to climate change. And so that just became an image that kind of stuck in my mind. Yeah. Robot mammoth.

ROSE:

People have proposed using robots to replace the bees that are dying. Walmart, yes that Walmart, literally filed a patent for this. Other people are working on robotic pets or robot therapy animals. PETA has even proposed replacing Punxsutawney Phil with a robot. Scientists in Switzerland and Japan have created robotic ants.

But can robots really replace animals? Do we actually know enough about all the things that bees or mammoths do to build a replacement?

EMMA:

Mammoths, they’re also going to maybe be wallowing and creating little depressions. They’re certainly leaving big piles of poop everywhere that move nutrients around in really complex ways. Obviously, herbivores aren’t just big lawnmowers; they’re doing tons of other stuff. So if you want to replicate a single function, you could probably do that. If you wanted to replicate every function undertaken by an animal, I think our knowledge is just not good enough.

ROSE:

Now, I want to be clear that Kate is not arguing that animals and robots are the same thing.

KATE:

Obviously, there are some very different capabilities that robots have that animals don’t have. You can’t dictate an email to an animal, and a lot of animals are, you know, physically more capable than robots in terms of, like, walking around and staying on their feet. But I think that the analogy just helps us open our minds to new possibilities, both in terms of how we’ve used animals in the past, but also in terms of what else can we do if we use these supplemental skill sets and partner with them in what we’re trying to achieve rather than viewing them as a replacement?

ROSE:

Take the legal questions around robots, for example. We’ve talked on this show a lot about, like, okay, what happens if your robot hurts someone? And sometimes, in the scholarship and the press, people act as though this is a completely new idea, a conundrum that we’ve never encountered before. But of course… it’s not, right?

KATE:

Ever since the earliest laws known to humankind that we found etched on clay tablets, you know, there are rules for what happens if your ox wanders into the street and gores somebody to death. Who’s responsible for that?

ROSE:

The Laws of Eshnunna and the Code of Hammurabi, both from about the 18th century BCE, lay out rules about this ox goring question. They both say that the fault in this case kind of depends. If your ox was usually pretty chill and gored someone out of nowhere, then you’re not responsible. But if your ox was kind of a jerk and known to cause trouble (a “habitual gorer” as the tablets say) then yes, if you let it out into the town and it gores someone, that’s on you.

And that’s actually pretty similar to how a lot of modern laws generally consider animal liability.

KATE:

So for example, you know, if you’re a zoo and you have a tiger, and the tiger, you know, breaks free and eats someone in the zoo, you can’t just say, “Oh, well, we couldn’t anticipate that this would happen. We thought the tiger was really nice. We’re so shocked that the tiger caused an injury,” because tigers are known to be dangerous, right? So the zoo is going to be responsible for that no matter what. But if you have like a tiny little, you know, poodle that has never done anything aggressive in its life and suddenly bites someone on the street, then you might give the owner a second chance and not hold them strictly responsible for what happens.

ROSE:

In other parts of history, we’ve actually tried to hold the animals themselves accountable for their misdeeds.

KATE:

We’ve put animals themselves on trial for the crimes that they committed. We would put pigs, and donkeys, and rats, and locusts, and all these animals on trial to punish them for causing harm.

ROSE:

One of my favorite examples of this is in 1479, in France, beetles called cockchafers were put on trial for “creeping secretly in the earth” and the court ordered the beetles “banned and exorcized.”

KATE:

And now, you know, in today’s world, we don’t really view that as an appropriate solution to hold animals, you know, morally or legally accountable for the harm that they cause.

ROSE:

And in a lot of ways, it makes the same amount of sense to hold a robot accountable as it does to put a beetle on trial. And thinking about robots legally, the way we think about pets might be especially useful if we do wind up with robo-pets in the future. Which Kate says, is definitely going to happen.

KATE:

We are going to see robot pets. I’m sure of it. Like, you know, I already have a bunch in my home, but I think it’s going to really take off societally at some point too.

ROSE:

But again, Kate is not saying that these robots will replace pets. She’s not arguing that robo-dogs and real dogs are the same thing. They will just be another thing in your life, another kind of relationship. People today already have robot pets, right? There are robot dogs that people really, genuinely love. There are also stuffed robotic animals used in therapy contexts. Adding a robot relationship into your house really isn’t that far-fetched. And Kate doesn’t really buy the idea that having a relationship with a robot is somehow emotionally stunted or bad.

And again, we can look to our history with animals to explain why.

KATE:

When dogs first started becoming part of the American family, there were a few people who raised concern and psychologists were like, “Oh, this is going to replace human relationships, and this is an unhealthy emotional attachment to these animals.” But really, what we’ve seen happen is that people have kind of folded animals and pets into their social lives without that taking away from or replacing any human relationships. And I think we’re going to see a very similar thing with robots where they are a new type of relationship.

ROSE:

And this is a new type of relationship, not just because of the look and feel, of the mechanics of the thing. It’s also a new relationship because robots can’t really feel things. Some people might disagree with me on that, but I would say that robots, right now, don’t have emotions the way that other humans or other animals do. The robot can’t love you back in the way that a dog can. And there really are studies about dogs loving their owners.

But Kate says… that doesn’t matter.

KATE:

It might matter for some types of relationships, but reciprocity isn’t, you know, a requirement. And what we’re seeing in human-robot interaction research is that people are developing genuine emotional attachments to machines, even knowing perfectly well that the machines don’t feel anything.

ROSE:

If you are someone who keeps an eye on these stories and questions, there is a lot of hand wringing about all of this in both the published literature research and in the media. And a lot of it focuses on these questions of emotional growth or some kind of maladaptive relationship.

KATE:

And you know, the first question that a lot of people ask is, “Oh, is this going to replace, you know, my human relationships, or my kid’s friends, or whatever?”

ROSE:

But Kate argues that that’s actually not what we should be worrying about with these robots. The real thing that we should worry about is who is making these robots and what they want from us.

KATE:

Robots are a very persuasive technology, and they are designed, and built and, you know, deployed by corporations and perhaps even governments at some point. And you know, if you have a persuasive technology that is helping a user in health, or education, or whatever, you know, great. But the danger is when the emotional persuasion is trying to manipulate a user on behalf of someone else or to someone else’s benefit. And you know, every new technology that comes along, advertisers are trying to get their hands on and see if they can, you know, manipulate user preferences or behaviors. And social robots, I think, are going to be a new tool for that.

ROSE:

Imagine your robot pet slowly convincing your kids that they need the latest toy, which also happens to be made by the same company; who would’ve guessed? Or worse, imagine your robot pet being social, connected to Facebook, and suddenly spouting conspiracy theories, or misinformation, or racism. And this isn’t just a worry for pet robots; it’s for any robot we might have a relationship with in our homes.

KATE:

I’m not worried about them replacing us so much as I’m worried about the sex robot having compelling in-app purchases that try to take advantage of people.

ROSE:

A lot of this conversation so far has been about how we use animals, and robots, in our lives for our own human purposes. How we can replicate their functions for us without having to use an actual animal. How we can use this as a metaphor for the legal and ethical questions that come up. We’ve asked a lot about what robots and animals can do for us. But what can robots do for animals?

RAE WYNN GRANT:

If a real bear and robot bear were to meet, you know, the smell of the robot bear would have to be extremely convincing. Extremely so.

ROSE:

More on that, when we come back.

ADVERTISEMENT: BIRDNOTE

This episode is supported in part by BirdNote. BirdNote makes podcasts about – yes, you guessed it – birds!

On BirdNote Daily, you get a short, two-minute daily dose of bird. From wacky facts, to hard science, and even poetry. You will learn why penguin feathers don’t freeze when they come out of the water. You’ll hear about the scariest bird, in my opinion, the cassowary, and how it makes the lowest bird sound that we know of. You’ll even hear about an ancient bird skull found by an amateur collector that is like the mullet of bird archeology. Chicken-like in the front and duck-like in the back.

And now is a perfect time to catch up on BirdNote’s longform podcasts, Threatened and Bring Birds Back. You can find all of those in your podcast listening app or at BirdNote.org.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ADVERTISEMENT: NATURE

Flash Forward is supported by Nature.

Do you want to stay up to date on the latest in global science and research? I know you do; that’s kind of why you’re here. So subscribe today to Nature, the leading international journal of science. There are a ton of papers related to this week’s episode that you can find in Nature. Soft robotics, robotic drones to monitor animals, all kinds of stuff.

But the one paper that I think is really cool and I want to mention specifically is one in which researchers used a robot to help figure out how an ancient creature moved. The animal in question is called Orobates pabsti, which is like an ancient crocodile thing. What researchers did was they used three scans of a fossil of this animal and a connected set of fossilized footprints to build a robot version so they could see how it would move. I’m going to link to a video of that robot in the show notes. It’s really cool.

And Nature is offering a special promotion for Flash Forward listeners until December 31st. Get 50% off your yearly subscription when you subscribe at Go.Nature.com/FlashForward. Your Nature subscription gives you 51 weekly print issues and online access to the latest peer-reviewed research, news, and commentary in science and technology. Visit Go.Nature.com/FlashForward for this exclusive offer.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ROSE:

One of the reasons that I’m really interested in animals, and technology, and the overlap between them is that so often people act like the “natural world” and “technological world” are two totally distinct things. But they’re not.

EMMA:

The ways in which we relate to other species are often mediated by technology, increasingly so. And many of the solutions that people are proposing for how to improve our relationships with other species involve using technologies of one sort or another.

ROSE:

We use drones, and camera traps, and sensors, and satellites, and sometimes even facial recognition to maintain this relationship with animals; to study them, to watch them, to learn about them. And we don’t just use devices to study them, we also use these devices to manipulate them.

EMMA:

I wrote in my book about a drone that’s under development in New Zealand that would not only, sort of, locate animals, but it would locate undesirable non-native animals and then drop poison pellets. So it would be sort of like… it’d be like a death-dealing drone in that case.

And what I found so interesting in interviewing the guy is that one thing that he said was a feature of this is that humans wouldn’t have to do the work of killing, that there would be this sort of layer of remove because killing animals is emotionally taxing, right? Like, it makes you feel sad to kill animals. But if you can outsource it to a drone, then maybe you won’t feel as sad. And so, he saw that as a feature. I saw that as slightly troubling because maybe we’ll be less likely to question our project of killing a bunch of animals if we’re not actually having to do it personally.

ROSE:

Today there are already robotic animals all over the place; drones that look like birds, for example. And one lab is using robotic fish to terrorize real fish, but for a good cause.

DR. GIOVANNI POLVERINO:

Mosquitofish are small, silvery fishes that are busily everywhere, including their ponds in the city center or, like, fountains in parks. And the reason why we care for them is that outside of the US, this is one of the main pests for aquatic species, really. So they look very small, but they are actually predators.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Giovanni Polverino, an animal behavior researcher at The University of Western Australia.

GIOVANNI:

And so in Australia, where I am now, mosquitofish is one of the main threats for the biodiversity in the water.

ROSE:

As is so common with stories like this, the mosquitofish don’t have any natural predators in these places. In the past, when people would try and solve these problems, they sometimes wound up making them worse with a cascading set of imported predators. So instead of doing any of that, Giovanni is working on introducing robots.

GIOVANNI:

Robots help us because they don’t breed, we can control them, and we can even change what they do depending on what we need at the time.

ROSE:

And specifically, he’s designing a robot fish that looks like one of the mosquitofish’s natural predators.

GIOVANNI:

So if we copy that predator with a robot and we introduce the robot in Australia, mosquitofish are very well aware of these robots, that it’s dangerous, because in their DNA is encoded that those characteristics correspond to something that for centuries has killed them.

ROSE:

Now, the robot that Giovanni is working on does not actually hunt the mosquitofish and eat them. It is not actually a predator; it just looks like one.

GIOVANNI:

There is no way that you can put the mechanical artifact in a water body that is able to kill one by one all of these pests that are everywhere; that’s trying to empty the ocean with a spoon.

ROSE:

Instead, it just stresses the mosquitofish out a bunch.

GIOVANNI:

We have observed that it’s not needed to kill the animal. We can actually compromise its lifespan. We can compromise its fertility, its reproduction. And so the capacity of these individuals to then produce other individuals that will, you know, continue the next generations. So basically, by acting on one, we can prevent the others from coming.

ROSE:

This is true of humans, by the way. Stress makes it harder to reproduce for almost every animal. And not only does this predator fish-robot stress out the mosquitofish, it also can protect the native species.

GIOVANNI:

Our robot is capable of recognizing who is bad and who is not and interact as a predator with a bad guy and actually protect like a bodyguard to the good guy.

ROSE:

Right now all of this is happening in a controlled lab setting and the robot probably doesn’t look quite like what you’re imagining. It is not a standalone, tiny fish swimming around with a little computer in its head. The processing required for the robot to sense its environment, and move around, and see the mosquitofish is too complicated to fit into a tiny little fish robot just a couple of centimeters long. Instead, the pieces of the fish robot body are not attached to each other, they’re attached to a platform that manipulates each of them around using a magnet.

GIOVANNI:

And the platform is connected with two high-resolution webcams that are on top of that area, that is the eyes of the robot, that are the eyes that allow the robot to see the whole environment and figure out who is whom. And the webcam and the platform are connected to one another through a computer. That’s the brain. That’s where the information goes. And very quickly, it’s shuffled so that the robot can make a decision and then act.

ROSE:

I will post some pictures of this on the website in case you’re having trouble visualizing what this looks like. Taking something like this from the lab into the wild is a pretty huge leap.

GIOVANNI:

To move this into the environment requires several challenges. We are moving towards the direction, but what we have now is something that can be applied to a small area for, let’s say, like a little pool in which the water is relatively transparent and in which there are not many species. I would say like two, three, or four different species. This is not the norm, so we are moving towards applying this technology to real life. Before now, we’re really looking at specific targeted areas and for a small amount of time.

ROSE:

Giovanni has also used robotic fish to study things like how schooling fish make decisions. In another kind of fish, the zebrafish, they’ve introduced these robots not as a foe but as a friend.

GIOVANNI:

We were trying to integrate a robot in that society. Make a friend.

[clip from Finding Nemo: “Fish are friends, not food.”]

ROSE:

And doing this research with robots allows them to replicate the same thing, exactly, over and over again in a way that simply observing fish behavior doesn’t offer.

Creating these fish is a cool project because it’s inherently interdisciplinary. You need roboticists and biologists working together to build something that is convincing. And one thing that I was curious about is how you actually convince a fish that what it’s looking at is indeed another fish and not some weird imposter or, like, device thing. When it comes to something like a zebrafish, they have an advantage.

GIOVANNI:

Fishes are very different and it depends which species you’re looking at. There are fishes that do not have any vision at all. Fish that live in caves that have basically now renounced vision and they perceive the world in a totally different way. We have purposely chosen models, like species, that are good to answer our questions, so they rely on vision really. So these are fish that normally live on the surface of clear waters, so there is a lot of light. And they can even be colorful because they may use their own color to signal to the other something, right?

ROSE:

But what happens when you move on from, say, a zebrafish, an organism that is super common in labs and very, very well understood to something… else? What about animals that communicate mostly by smell instead of sight? Or sound?

RAE:

You know what’s so funny, I’m so old school that when I think of a robot, I think of a metal machine. So like, that’s the first thing where I’m like, “Well, that wouldn’t work because it’s obvious.” So, you know, like physically, there would have to be like a true physical match.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Rae Wynn Grant, a wildlife ecologist and the host of the podcast Going Wild. And Rae’s current work is on big animals. Like bears.

RAE:

And in doing that, it teaches me a lot about, like, all the other things in the ecosystem, right? Because top predators often control or engineer and manage ecosystems.

ROSE:

Today, Rae studies backcountry bears. So, not the bears that are going through your garbage or showing up on your porch cam.

RAE:

The ones I’m studying are the ones that have the least interaction with humans. Maybe they’ve never interacted with a human ever. And I want to observe their behavior so that I can properly compare it to the ones that are, like, on the outskirts of town.

ROSE:

And to find these reclusive bears, she heads out into the backcountry.

RAE:

It’s really fascinating; feels like a big privilege. It’s exciting. You know, there’s all this adrenaline. And also, I will be completely honest, sometimes it’s super boring. Sometimes it is so boring. Sometimes I am looking for bears for 10 days and not finding a single one. And although nature is awesome and beautiful, like, you know, there’s boredom that creeps in too.

ROSE:

But sometimes, she does see a bear, which is awesome. And also terrifying. Because these bears have no real fear; they have basically no natural predators and they are not social. They might not really appreciate being watched. So Rae has to be careful.

RAE:

People will ask me a lot, like, “Aren’t you scared?” And I’m like, “Of course I’m scared! Are you kidding me? Like, I could die.” So yeah, I’m scared, you know? But I’m being careful and I know exactly what to do and what not to do. And you know, there’s always this element of chance, and there’s definitely risk involved in me going into remote places and observing these animals.

ROSE:

So after all this time observing these bears, I wanted to know the obvious question, which is, how would she make a bear robot?

RAE:

There would have to be, like, fur. And it would have to smell a certain way. Bears have an incredible sense of smell. One of the best in the entire animal kingdom. Scientists have not been able to properly measure how far away bears can smell because every time they measure it, it looks like they’re not reaching the maximum. You know, there are some estimates that say bears can smell from five miles away, right? Like, that’s wild. And so, up close, like if a real bear and robot bear were to meet, you know, the smell of the robot bear would have to be extremely convincing. Extremely so.

ROSE:

The bears that Rae studies, again, are not social. They spend most of their time alone.

RAE:

So it’s not like they’re like, “Oh yes, another bear is here! Awesome! Let’s hang and do stuff. Let’s play!” That wouldn’t be a part of it. So the robot bear would have to make sure that it was programmed to understand that there is, like, a territorial nature between these animals and to, like, not push it right? Because then it would get in a fight and then it would be exposed as its true robot self.

ROSE:

And if you really wanted to go 100% all in and make a fully convincing bear, you would have to figure out how to make it hibernate.

RAE:

It couldn’t need, like, a recharge during that time. That’s like the whole point. Real bears don’t eat, they don’t drink. You know, they don’t pee, you know, they don’t poop, they don’t do any of these things. They recycle their waste inside of their bodies. Their heart rate slows down, their breathing slows down, the metabolism slows to a crawl. I would argue that a really good robotic bear would also need to have multiple settings, you know, so that it could have that, like, active, in-the-mix setting and then a really pared down energy-saving setting.

ROSE:

But what if you didn’t have to convince other bears, you just had to convince people? One of the most compelling arguments, in my opinion, for creating really convincing animatronics is for use in zoos. At this point, I have done a fair amount of reporting on animal welfare, research, and zoos, and I have slowly come to the sort of sad conclusion that, personally, I just can’t justify capturing and keeping animals in enclosures for human entertainment.

EMMA:

So the two arguments that the zoos make are essentially… the first part is that the animals are pretty happy and the second part is that their captivity is justified by all these great outcomes.

ROSE:

And it was actually Emma’s recent book that finally put me over the edge from feeling very deeply conflicted about zoos to pretty firmly opposed to them. At least in their modern form.

EMMA:

Many animals aren’t happy in captivity, and also the, sort of, benefits of zoos have been massively oversold in terms of creating conservationists, or creating a public that cares about endangered species, or even doing the work of conservation, breeding, or reintroduction. There’s a lot of greenwashing involved in these institutions, and it’s not to say that no zoo has ever done a good thing. You know, there are some reintroduction programs that have involved zoos that have been successful. But by and large, most zoos are not doing this kind of work. And most animals that are in zoos are not part of these programs.

ROSE:

In her book, Emma argues that zoos could be reinvented and they could still be places for families to go and to learn about and experience nature without having to sacrifice the mental health of so many living creatures.

EMMA:

I talk about how, like, we should shift these zoos to be more like gardens and to encompass biodiversity as a whole, not just the animal kingdom. So, I think that in that context of seeing zoos transition from being something that’s, like, bear in a box, lion in a box, tiger in a box, to something that’s much more like, “Here is the wonderful world of biodiversity. We have all of these wonderful plants, and we have this very small captive breeding program for this turtle species that’s local to this area.”

ROSE:

And maybe in this version of the future zoo, you can also pet an animatronic tiger or bear.

EMMA:

I think that could actually work. And part of the reason I think that is that when I was a kid, I went to the La Brea tar pits and they had animatronic animals at the La Brea tar pits, and I flippin’ loved them! Like, I loved them. And they were a very strong childhood memory for me.

So I think that fake animals… you know, what’s the difference between an animatronic animal and those, like, lovely taxidermy displays at the New York Natural History Museum that people love so much? Nothing except some movement.

ROSE:

Even Rae, who spends all of her time trying to interact with and learn about living biological animals, nonrobotic bears, saw some potential in this idea.

RAE:

It’s so weird because I’m like, “Oh, I wouldn’t want to do that.” No offense to whoever thought of this idea because I see it as a solution. But you know, I don’t think I personally would be interested. But you know, it’s interesting enough. Like, honestly, I really feel like, “Why not?” Why not? And I could also see a whole group of people actually being more comfortable with that idea than anything that does have real animals.

You know, there’s a whole bunch of folks – and let’s be honest, plenty of people, even in my family and friend group – who are kind of like, “I would absolutely never interact with a wild animal. You’ve got to be joking. I wouldn’t even be near one, even in a car,” you know? So I think that that could really serve groups of people who are curious enough, and like the idea of animals, and are supportive of conservation, but also are, like, super risk averse, you know?

ROSE:

You could program these animatronic animals to interact with the public in ways that you can’t have with a zoo creature. So, imagine you’re walking along and a cheetah would waltz out from the tall grass and walk right up to you, and you could pet it!

Now, I told a friend about this idea, and his answer to this proposition was really interesting to me. He basically said that would not be appealing to him because he would want some kind of randomness. Some serendipity. Like, not every single person gets the cheetah walking out from behind the grass. It’s like when you go to those butterfly enclosures and if a butterfly lands on you it feels special. But if it was a robotic butterfly that was programmed to land on everyone, it wouldn’t feel that special. He would want it to feel organic, natural, kind of unpredictable.

EMMA:

I think that if you want that feeling of serendipity or that feeling of having a lucky encounter, then you should be going to your local, like, landfill to look for cool birds. You should be going to your local wildlife refuge, or you should be going down to the canal to see if you can see a muskrat. You know, looking for animals that exist around us that are maybe not lions and zebras, but they’re cool. And when you see them in person and it’s an unplanned occasion, it can be extremely memorable. And then you could have the animatronic zoo be a much more reliable way to apprehend the otherness of other species.

ROSE:

In thinking about designing these zoo robots, I also got to thinking about accuracy. If the goal of this animatronic zoo is to educate the public about an animal, you might design the robot slightly differently than if the goal is for the robot to fool other members of the species, right? You might, for example, accentuate certain features that help you identify an alligator from a crocodile.

EMMA:

Well, it makes me think about scientific illustration, right? So, scientific illustration is this fascinating art form because not only do they strive for accuracy, they also want to include all of the important features. So they’ll do things like, you know, they’ll show a plant in flower, but also in fruit on the same image, even though that would never happen in nature, so you can see all the important stuff. And so, I imagine that building a robot version of an animal would be a little bit like drawing a scientific drawing of the animal in that there might be occasions where accuracy is second to, sort of, including or highlighting important features, making things salient.

ROSE:

And while we are really not close to humanoid robots, or even really robots that can replace animals fully… there are some interesting robots that can look and act enough like animals to do some of the things that we just talked about.

EMMA:

Can you imagine being, like, an adult condor and then finding out that your mother was just a puppet?

ROSE:

And we’re going to talk about that when we come back.

ADVERTISEMENT: DIPSEA

This episode is supported in part by Dipsea.

Sometimes, doing less can lead to so much more. Dipsea Stories believes in less analyzing and more feeling your feelings. Less stressing and more easing into things. Less scrolling and more savoring the moment. Less pressure and more pleasure.

Dipsea Stories is an app full of sexy audio stories, and they now have brand-new written stories too. No matter who you are or what you’re into, Dipsea helps bring these stories to life, anytime, anywhere. You can close your eyes and let yourself get lost in a world where only good things happen and pleasure is your priority. Explore your fantasies in a safe and shame-free way.

There are hundreds of stories to choose from and they release new content every week so there is always more to explore. And they also have wellness sessions to help you wind down and explore, and sleep sessions to help you drift off. So far, as far as I can find, they do not have any robot-on-human or human-on-robot or robot-related scenes or stories, but hey, maybe that will happen sometime in the future.

For listeners of Flash Forward, Dipsea is offering an extended, 30-day free trial when you go to DipseaStories.com/FlashForward. That’s 30 days of full access for free when you go to DipseaStories.com/FlashForward.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ADVERTISEMENT: BETTERHELP

This podcast is sponsored by BetterHelp.

Is there something interfering with your happiness or preventing you from achieving your goals? Like, I don’t know, the news, climate change, the pandemic, the increasing realization that powerful people will simply refuse to make the world better for others even when the option is right in front of them? No? That’s just me for today? Okay.

Well, if you are looking for some kind of help for whatever it is that you’re stuck on, BetterHelp might be a good option for you. BetterHelp assesses your needs and matches you with your own licensed professional therapist who you can start communicating with in under 48 hours. They offer a broad range of expertise and you can log in from anywhere in the world and send a message to your therapist. You will get timely and thoughtful responses, plus you can schedule weekly video or phone sessions. It’s not a crisis line, it’s not self-help. It is professional therapy done securely online.

Plus, BetterHelp is committed to facilitating great therapeutic matches, so if you don’t like your therapist or it’s just not a good match, they make it really easy and free to change therapists if you need to.

Visit BetterHelp.com/FlashForward and join the over 2 million people who have taken charge of their mental health with the help of an experienced professional. And BetterHelp is offering a special deal for Flash Forward listeners. Get 10% off your first month at BetterHelp.com/FlashForward.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ROSE:

The robot that made me decide to do this episode is a dolphin. A robot dolphin. It weighs 550 pounds and it lives in Hayward, California, and I really, really wanted to meet it but the company, Edge, never responded to my emails. So if you’re out there, please let me come meet this dolphin! But I’ve watched a lot of footage online of this dolphin and it is shockingly convincing. I’ll post videos of it on the website in the post for this episode.

Edge, this company, makes robots usually for movies. They created the robots for Free Willy, Deep Blue Sea, and Anaconda. But now they’re taking that technology to the aquarium to potentially replace dolphins there. Now, the robot in question here is very expensive. Like, $3 million to $5 million expensive. But when you compare that to the cost of keeping a living dolphin, and I mean both the literal cost in dollars and the ethical cost, I can absolutely see how this would be worth it.

And in this future, you’d go to this aquarium and you would now, right? You would know you were looking at a robot, but you might still get the same things out of it. But when we start to put robots out in the wild in places where we really want them to fool their fellow creatures, as opposed to being a tool for humans and human education, that’s where I start to feel a little, like… I don’t know. Just kind of weird. And it’s not just Giovanni and his robot predator fish, there are other people doing this kind of sneaky robot work.

[clip from Nature: Spy in the Wild:] “The world is full of extraordinary animals. But how well do we really understand them? What do they actually think and feel?”

This is a nature documentary show called Spy in the Wild.

“To find out, a team of spy creatures is going undercover. They not only look like part of the family, they behave like them too. Armed with the latest camera technology, they are going to travel the globe to understand the true nature of the animals they meet.”

The premise of this show is basically what you just heard, they build these robot animals and embed them with wild animals. And I will say, the robots on this show are surprisingly convincing; they look pretty good. It’s very obvious that they’re a robot, but they’re better looking than I expected them to be. They are good enough that, in some cases, according to the show, the animals seem to accept these robots as fellow penguins or monkeys. In fact, in some cases, the animals seem to really accept them. Like in one episode, a penguin seems to try and partner with the robot.

“Rockhopper cam has found an admirer. The penguin displays to show he’s keen. She might be a robot, but it’s still love at first sight.”

And in another, a dolphin offers the robot dolphin a present.

“He picks up a mangrove seed and presents it to Spy Baby. Offering gifts is common among dolphins, but Spy Baby can never be the companion he needs.”

And the one that made me feel… just, a lot of weird feelings is with a troupe of langur monkeys in India. They give these langur monkeys a robot baby monkey. And at one point, one of the monkeys drops the robot baby out of a tree. And it just lays on the ground, right, because it’s a robot. And this seems to be very distressing to the other monkeys. One runs up to the robot, picks it up, and cradles it.

“And this langur seems to believe our spy baby has died.”

At this point in the show, the robot monkey baby is laying on the ground and is surrounded by other monkeys and they’re all looking at it.

“Then, something extraordinary happens.”

Some of the monkeys come up to it and they, like, very gently touch the robot.

“The monkeys gather around the motionless spy creature as if it is a real baby.”

As they look on at this dead baby robot monkey, the real monkeys hug each other. One cradles a living adolescent in a very protective, maternal way.

“A quiet and contemplative mood descends on the colony.”

Okay, look, yes this is a very melodramatic show and it is clearly trying to present a certain narrative. We don’t know what they cut out; we don’t even know if any of the footage we just saw is, like, actually related to the baby monkey. I don’t really know how exactly legit it is. I did run the clip by two primate biologists, Dr. Michelle A. Rodrigues and Dr. Lydia M. Hopper, to see if these behaviors that you see in the show are anything like the way that primates behave when a baby dies. And they both said that this documentary footage is definitely overblown.

Lydia and Michelle both agreed that what the footage shows was monkeys being curious and unsure about a weird new object in their midst, not monkeys mourning something they thought was a real baby. Now, there is some really interesting research about how primates mourn and grieve, which we don’t have time to get into right now, but I will talk about more on the bonus podcast this week.

But even knowing that this footage doesn’t match the narrative presented by the show, I still found this clip very upsetting. I don’t like the idea of tricking these animals into accepting a, kind of, funny-looking individual into their group so that we can spy on them. If it were humans, and we gave a human a baby robot, and they believed it was real, and then mourned that baby, and then we were like “Surprise! It’s actually a robot,” that would be terrible! We would not think that was okay.

I did ask Lydia and Michelle about this, about how they felt ethically about the premise of this monkey robot, even if the actual execution was lacking. Michelle said that she personally would not want to play any sort of tricks like this on monkeys, especially something that involves this, kind of, uncanny valley, trying to figure out if something’s real or not. She said it seemed cruel.

I often return, when I think about animals, to a book by Dr. Sunaura Taylor called Beasts of Burden. The book is about the ways that animal liberation and disability liberation are connected and intertwined. And when I watch this show, Spy in the Wild, I watch these animals look at something and go, “Huh, yeah, you’re kind of weird, you’re a little odd, you’re a little different, but that’s okay. Here’s a present!” Or, “Maybe we could mate anyway.” I think there’s something really lovely about these animals accepting the robots that look different, that don’t move quite right, that are a little slower, a little odd, that maybe smell a little funny. And to then have that acceptance used against them as a way to infiltrate their worlds and spy on them… I don’t know. I just don’t like it.

I personally think that humans should always know if they are talking to a robot or to a person, and I think that animals should know too! It feels mean, and kind of rude, frankly, to trick them like this.

EMMA:

I even feel that way about the puppets they used to raise the condors during the condor captive breeding program. Like, I feel sorry for those baby condors that were raised by puppets. Not that they’ll ever necessarily know, but can you imagine being an adult condor and then finding out that your mother was just a puppet?

ROSE:

And I think that one of the reasons I’m so drawn to talking about animals and technology on this show is that these questions really make me think about what we consider acceptable to do to the living creatures that we share the world with. Like, right now we seem to think that it’s totally fine to put hidden cameras in an animal’s house and record 24/7. But obviously, you could not do that to a person.

EMMA:

Why not just assign every single cougar its own personal drone? And then it could send a text message to the Department of Transportation when it comes near a highway and they could halt traffic.

ROSE:

We talk on this show all the time about not building a totally pervasive surveillance state, but it’s somehow okay and even noble to do that for animals?

EMMA:

And I think, to me, this is a really difficult area for me to find my way through because, on the one hand, all that data that you would get from all of this constant monitoring could really allow us to do this sort of really nuanced coexistence with other species. Like, we really could have a subway that automatically shuts off when a fox wants to cross the tracks because we know that the fox is coming because we have some sort of monitoring system in place.

But then there’s this other part of me that really just wants these animals to be able to be unobserved and to be… To me, there is a sense in which them being monitored all the time somehow infringes on their rights to just hang out and not be monitored.

ROSE:

Humans are animals, but it’s true that we are slightly different from a lot of other animals on this planet. And on the one hand, you might say, “Well, we got these animals into this mess. It is our fault that these cougars are in trouble in the first place, so we have a duty to help them.” And that might be true, but I am not convinced the answer, the way that we help them, is by becoming further intrusive into their lives.

When systems fail humans, we don’t generally think that the answer is to then follow those humans around 24/7 with cameras to make sure that they stay safe, right? I mean, I do think that some people in the world might think that, but on this show, on Flash Forward, we do not think that. More surveillance does not necessarily mean more safety, for humans or animals.

It strikes me, in thinking about the ways in which we just do stuff to animals without really thinking about it at all, that humans are, like… greedy.

EMMA:

We want so much from animals. We want them to be noble and totally apart from humans. But then we also want them to be our friends and, like, we want to pet them, and hug them, and love them, and we want to take pictures of them. But we also want them to live forever, and not die, and not go extinct. We are very demanding of animals in this world. And in some ways, I feel like creating robots could, in some cases, take some of that pressure off the real animals.

ROSE:

The way that humans often think about animals, I think, is very weird. We can be very demanding, right? Asking all of this stuff from them, I think a lot of people also don’t really know how to think about their agency and personhood.

KATE:

We have this very, on the face of it, very hypocritical relationship to animals.

ROSE:

Not every culture and not all people think about animals the same way, so we can’t really generalize across all of humans, but I think it’s fair to say that in the West, in the dominant colonial worldview, we think some animals are worth protecting, and saving, and maybe even giving certain rights to. Pets, dogs and cats for example, are treated like people, like family. Certain primates that look a lot like us, I think, are more and more often considered off-limits for certain kinds of research and certain kinds of treatment. And plenty of animals are not for eating, at least for specific people or in specific cultures. But when you try to find a common thread between the animals that people care about most, it’s often really hard to figure out what links them.

KATE:

It’s always been really interesting to me to look at the history in, you know, Western society, the history of the animal rights movement because it’s just so clear that we’ve never followed any type of consistent moral philosophy that cares about whether animals feel pain or whether animals suffer.

ROSE:

Take whales for example. Today, whales are one of the species that I think most people think of as untouchable. The idea of mass whale hunting is often used as an example of one of the terrible things that humans do. People care a lot about whales. But that wasn’t always the case.

KATE:

People did not care about whales at all. Like, whales were being slaughtered all over the place. And then one day a researcher discovered that the whales could sing, and… I think it was Greenpeace. They took the recordings and they made, you know, a movement out of this. And once people heard the beautiful song of the whale singing, they’re like, “Oh yeah, we gotta save the whales,” and then the Save the Whales movement took off. So, you know, the whales were saved, not because they feel anything but because they could sing and people related to that.

ROSE:

In Beasts of Burden, Sunaura Taylor points out that people didn’t really care that much about primates being used in medical research labs until those primates were taught to sign. Then, suddenly, they were like us, they could communicate with us, and all of a sudden using them for certain kinds of research in tiny cages in labs was seen as much more horrifying. The only thing that changed was that we taught them a tiny bit of sign language.

KATE:

And what human-robot interaction research is showing is that we do the same thing with robots, where if a robot looks appealing to us or acts in a way that we recognize and relate to, then we have empathy with that robot.And it’s kind of depressing to realize that that’s kind of how we’ve treated animals throughout Western history as well, and that this human-robot interaction research is basically holding up a mirror to what we really do care about in non-humans.

ROSE:

I’m sort of obsessed with the ways in which we can and can’t analyze human intelligence. We’ve talked about this on the show in the past a lot, about the history of using animals in labs, and how people used to think that only humans could feel pain or have personalities. But scientists are learning more and more every day about the ways that animals have incredible senses, really fascinating ways of manipulating the world, of creating their own forms of technology, or interacting or communicating.

Most roboticists will say that we are nowhere close to general AI; AI that can actually replicate human general intelligence. But I think that the idea that robot intelligence is like animal intelligence is also, kind of, fraught be we don’t even understand animal intelligence yet so we definitely can’t replicate it.

Last week, we talked about the ways in which using humanoid robots as a hypothetical way of talking about human oppression can be problematic because it can sometimes ignore all the ways in which we are terrible to real, living humans right now. And I think that this can also be true of talking about robots and animals too. We do terrible things to animals today. Truly terrible. In some of those cases, maybe we should replace those animals with robots that can do the same thing without suffering.

In other cases, I hope that we can keep the living creatures we share this Earth with in mind when we are inventing stuff or talking about the ethics of care, and family, and relationships. You often hear roboticists argue that robots are a tool; they’re a thing you can make to do a job. And I think many people used to think of animals in the same way; they were things that you could make do a job.

I think, more and more, that idea, for many people, is being replaced by the idea that animals are sentient, that they have intelligence, that they have personalities. And maybe one of the jobs that robots can do is actually help us see that more and be better to animals.

KATE:

Possibly we are at this unique moment in time where, because we’re going to realize that we care more about certain non-feeling robots than we do about living, breathing animals like a slimy slug, perhaps it’s a moment to rethink whether we want to continue to default to only caring about the things that we feel an attachment toward, or whether we want to, kind of, put our money where our mouths are and actually care more about which animals suffer and feel pain and protect more them more broadly.

And I’m hopeful that, perhaps as people start developing relationships to robots that are clearly not alive and clearly don’t feel, I’m hopeful that we might start to rethink what our relationships mean and rethink how we’ve done animals dirty and continue to do animals dirty, at least compared to what we think we care about.

ROSE:

And that is the last episode of Flash Forward as we all know it. I know I’m supposed to say something at the end of this episode, but I’m honestly not quite sure what to say that can adequately cap this whole thing off.

Flash Forward has been pretty much my whole life for the last seven years and it’s been an incredible experience. I get to call up the smartest, most interesting people in the world and I get to talk to them about how the future could look. I mean, it’s genuinely the dream job. Flash Forward has introduced me to incredible people, some of whom I get to call friends now. It has offered me opportunities all over the world. It allowed me to write a book, my very own book! Which, by the way, makes a great holiday present if you’re doing some last-minute shopping while you’re listening to this.

When I started Flash Forward, I did not have a grand ethos about the future. I just thought it would be fun and cool to blend audio fiction and journalism and to think about scenarios, and think about the future. And it totally was. But over the years, I’ve really come to actually believe that doing this thing – thinking about the future in weird and creative ways – can actually make the world better. There is some psychology research showing this, showing that people who practice imagining the future are happier, they feel less anxious, they feel more ready to take on what comes next.

But even beyond that, being able to explore possibilities, to think critically about what we want to have happen, to identify the places that we can make change, the ways that we can push the future in the direction we want to go… I think that’s how the world actually does get better, right? Things are pretty bleak right now. I don’t need to tell you that. There’s climate change, rising white nationalism, gun violence, the continued pandemic. It can feel, at least to me, like the future is hopeless. But there is real power in combining imagination and action, in thinking about what we want, and then identifying the ways that we can go out and get it.

I sometimes say in the press when I do interviews about Flash Forward that my hope with the show is to give people the tools to imagine the future. But it’s probably more accurate to say that Flash Forward has been a way for me to try and get those tools myself and then share them with you. In a lot of ways this has been my lifeline, the way that I try and make sense of the world, and push for something better, and then maybe, hopefully, bring other people into that conversation too.

So I hope that over the last seven years, you’ve also felt some solace here in these airwaves, knowing that there are people out there thinking about what tomorrow could be like, and working towards it. Knowing that you can be part of that, in all kinds of ways. Knowing that the future hasn’t happened yet and that you get to have a say in how it does.

Flash Forward isn’t dead. It feels weird, like I’m giving a eulogy for the show. We will be back next year with something completely new and completely different. It will still be about the future and about this idea of imagining what’s possible and how to reach it. I don’t know exactly what it’s going to look like, and I’m trying to give Julia and I a little bit of space to not jump to conclusions about what it will look like. We’re going to do a bunch of exploring in trying to figure that out, but that’s going to be really fun and I’m excited about it.

If you want to keep up with the show and get updates as we work towards the next version, you can sign up for the newsletter. I will link to that in the show notes and it will also be on the website.

Again, please go to FlashForwardPod.com/Survey and take the survey. And until I’m back in your ears, I hope that you continue on in the Flash Forward spirit and make better futures.

[Flash Forward closing music begins – a snapping, synthy piece]

Flash Forward is hosted by me, Rose Eveleth, and produced by Julia Llinas Goodman. The intro music is by Asura and the outro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Mattie Lubchansky. The voices from the future this episode were played by Richelle Claiborne, Henry Alexander Kelly, Shara Kirby, Anjali Kunapaneni, Chelsey B Coombs, Tamara Krinsky, Keith Houston, and Jeffrey Nils Gardener. The music for X Marks the Bot was composed by Ilan Blanck. You can find out more about all of those amazing people in the links in the show notes.

Also, huge thank you to Amanda McLoughlin at Multitude Productions who has handled ad sales for Flash Forward for the past couple of years.

If you want to discuss this episode, some other episode, the future in general, or the future of Flash Forward, you can join the FB group! Just search Flash Forward Podcast and ask to join. Just a quick heads up that I am going to be migrating the Facebook group over to Discord in January to try and minimize the show’s, sort of, tacit support for Facebook as a company. You will get a link to that Discord in the newsletter I mentioned. I’m saying this because if you are a listener who doesn’t have Facebook and doesn’t want Facebook but you want to participate, signing up for the newsletter is how you’ll get that link; the easiest way to get that link when it happens.

If you want to support the show as we enter into this new phase, it is a great time to do so because it will help me keep Julia and others on board and paid properly. You can find out more about all of that at FlashForwardPod.com/Support.

And this is the last time that I will ask you to rate and review the show! It really does make a difference. I do read all the reviews; the good ones and the bad ones. So if you go leave a review, I will read it.

Okay! Thank you all so, so much for listening. And I will see you, or hear you, in another tomorrow.

[music fades out]